To see his obituary please click the link provided.

Danger—Alaska Highway Builders at War

Danger and death confront soldiers at war, and make no mistake about it, the Army dispatched the Alaska Highway builders to war. Two soldiers in the 35th died when they rolled their grader over a bank. 1st Lt. Small of the 18th wrecked his jeep getting around a bridge under construction. His men found his body under the jeep—back broken. A cook in the 340th torched himself by pouring gas on a lit stove burner; died on route to the hospital. Tech Sgt. Max Richardson of the 340th died in his wrecked truck. And an unknown officer, probably a second lieutenant, training his men to field strip a machine gun, accidentally shot Staff Sgt. Whitfield.

Soldiers got sick, injured and dead on the Alaska Highway in 1942. Given the working conditions, the food, the standard of personal care and the sanitation, that shouldn’t come as a surprise. Soldiers exchanged germs. Everybody experienced dysentery—some jaundice. And the dangerous work lacerated skin and fractured bones on a regular basis.

Company morning reports refer constantly to men on sick call, men moving to this medical facility or that for treatment… The reports don’t provide details or even diagnoses, but they make the frequent need for medical care very clear.

The soldiers drove vehicles with cannibalized parts, sometimes without brakes. They patched broken tools together with wire, tape and ingenuity. They worked brutal hours swinging axes, felling trees, slewing vehicles through mud and along steep mountainsides. Soldiers at war, they got wounded and, in the most dramatic cases, they died.

We know about death on the highway from various sources–regimental histories, interviews, memoirs, letters… We have examples, not exhaustive records. We have said many times that the three black regiments were ghosts, their role in the great project obscure. And we have considered the reasons for this—the preference of reporters and cameramen for following the white regiments, the Corps’ tendency to ignore the contributions of the black regiments, the fact that less educated black troops left fewer letters and memoirs. Perhaps the saddest consequence of this fact is that the fragmented history of death on the highway mentions only a very few of the black man who made the ultimate sacrifice.

More on Army Medical Care in 1942

At The Million-Dollar Valley

At the million-dollar valley, the North Country collected three bombers from the US Army Air Corps in January 1942. Flying over the Far North required a unique skill set. But the Air Corps didn’t know that, and nobody thought to ask the bush pilots who did know. They were, after all, the Air Corps and the bush pilots were, after all, just bush pilots.

In the run up to WWII Canadian contractors had installed a string of airfields from Canada north to Alaska, located one of them at Whitehorse, Yukon. A month after Pearl Harbor, the US Army Air Corps tried to use the airfields.

LInk to another story “Marvel Crosson—Lady Bush Pilot”

On January 5, a flight of fourteen B-26 Marauder bombers took off from Boise, Idaho and confidently headed north. They flew to Edmonton, at the edge of the North Country, without incident. Eleven days later they took off again headed for the Canadian airstrip at Whitehorse, Yukon.

The pilots carried pencil drawn maps. They had no access to navigation aids. They had plenty of access to British Columbia winter. And they had no idea what they were getting into. Miraculously, eleven of the Marauders made it to Whitehorse.

Three others got lost.

By evening, low on gas, with no idea which way to go, forced to low altitude by blowing snow, they decided to crash land; began looking for a suitable location—not easy to find in the mountains.

At the million-dollar valley, British Columbia graciously offered a solution. The pilots gratefully accepted the broad, fairly flat valley covered with snow. Two of the pilots dealt with the snow by keeping their landing gear up, coasted onto the valley floor like monster toboggans. The third pilot, worried about landing speed, put his wheels down to dig into the snow. Gear up worked better.

The wheels did, indeed, dig into the snow—too deep and too quickly. The marauder flipped up onto its nose in a spectacular crash, injuring the pilot and copilot, leaving the rest of the crew merely shaken up.

A search the next morning failed to find the valley, but the next day a flight of P-40E fighters, also headed to Alaska, spotted the three planes. Bush pilot, Russ Baker, as grizzled and North Country experienced as Bush Pilots come, flew in with his Fokker, landed on skis and flew the injured men out to Watson Lake. It took three more days to get the rest of the men out.

Crews went in and salvaged parts from the planes, but the planes themselves became permanent residents of the valley, named “The Million-Dollar Valley” after the value of three B-26’s.

Photographing Alaska Highway Builders

Photographing the soldiers of the 97th on the Highway in Alaska, Sgt. William Griggs had a unique mission. A regiment with 12,000 black soldiers naturally included some with unusual backgrounds and skills. The 97th included Griggs.

Griggs father made photography a hobby and growing up in Baltimore, Griggs learned to love it too. After high school he went on to hone his photographic skills at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania.

Came WWII, Griggs, like millions of other young men, found himself, quite unexpectedly, in the United States Army. A black man, Griggs also found himself in a segregated regiment. When the commander of the 97th learned of Griggs’ special skills, he promoted him and made him the official regimental photographer.

In April 1942, Griggs scored a leave, went home to get married. But, between marriage and honeymoon, a telegram urgently summoned him back to Eglin Field. With the rest of the regiment Griggs travelled by train cross country to the Seattle Port of Embarkation where they crowded into an old troopship, the USS David Branch, and sailed north to Valdez, Alaska.

The Army put a great deal of effort into keeping black soldiers away from the local population and declared Valdez strictly off limits–except for Sgt Griggs who had permission to go to Valdez for film and photographic supplies.

Sgt Griggs served in the Headquarters and Service (H&S) company, first in Valdez, later in the interior. The photographs he took remain some of the best and most dramatic taken anywhere on the Alaska Highway Project. After the war Griggs travelled, spoke, shared his photos widely, did interviews—became an important resource for Alaska Highway historians.

In an PBS interview, Griggs remembered the Army’s attitude toward black soldiers. “It was thought that they couldn’t learn how to operate complicated construction equipment like bulldozers and things like that.” But the men learned and became, among other things, outstanding catskinners.

And Griggs remembered food. Sick of canned chili, the soldiers took can after can to a nearby native village to trade for smoked salmon. “Finally, the Indians told us to bring something else to trade. They were tired of the chili.”

In a later interview he remembered mosquitoes. “There were one thousand per square yard. We slept under netting and wore WWI hats which were covered with netting to protect our faces.”

And he remembered, above all, the cold weather when the regiment stayed in Alaska into the winter. A lieutenant and a black enlisted driver, in February 1943, headed out in a Studebaker truck to pick up gas and diesel fuel. When the truck broke down, the Lieutenant walked ten miles for help, but when help returned they found the driver frozen in a sitting position.

A Mortal Threat and the Irony of History

A mortal threat to America from Japan, inspired Canada to build the series of airfields north to Alaska known as the Northwest Staging Route. The NWSR would at least get some defense material north, and it established a rough path for the land route to come—the Alaska Highway.

By 1943 the Japanese, permanently on the defensive after the naval battle at Midway decimated their carrier fleet, ceased to be a mortal threat to Alaska. In Europe, though, Hitler had long since unleashed Operation Barbarossa, a massive attack on the Soviet Union. In the beginning the disorganized and under-equipped Russians couldn’t offer much resistance, but winter came to their rescue. Winter didn’t turn the Germans back but that first winter stopped them temporarily.

Link to another story “Canada Went to War Early”

Allied leaders, Roosevelt and Churchill, didn’t care much for Stalin and his Soviet Union. But in a crisis, the enemy of their enemy was their friend. The Soviet army faced three German armies across a massive front, Germany’s only real opposition. But without massive resupply, especially warplanes, the Soviets would crumble.

“The Arsenal of Democracy” the United States could churn out warplanes. Under Lend Lease they would ‘sell’ them to the Soviets, worry about getting paid later. But getting them from the United States to the Soviets on Hitler’s Eastern Front posed a problem. The direct route from the United States to the Soviet defenders crossed the Atlantic and the heart of Hitler’s empire.

Canada’s Northwest Staging Route offered a solution. If pilots couldn’t get planes around the world, they could get them over the top. American pilots flew the bombers and fighters from plants in the lower 48 up to Edmonton, Alberta and then on up Canada’s string of airfields to Fairbanks and finally to Nome. Russian pilots would take them there, fly them over the narrow Bering Strait and on across the vastness of Siberia to where they could pound the German armies besieging Moscow, Leningrad and Stalingrad.

Ironically the Northwest Staging Route did more to win the war than the Alaska Highway. The Highway remained critical, but primarily because it gave the Canadians better access. Canada worked on the NWSR throughout the war; ran telephone lines between the airfields, improved radio communication, enlarged runways…

Fred Spackman worked on the airfields of the NWSR throughout the war, left many photographs to his daughter who graciously shared them with us. Link to the Northwest Staging Route group on Facebook

Defending America, Building the Alaska Highway

Defending America. Our two-book series We Fought the Road and A Different Race tell a story you’ll want to read. We Fought the Road on Amazon A Different Race on Amazon

In 1942 black and white soldiers built a land route 1600 miles long through the most difficult country on earth in just eight months. The Army desperately needed to get the material of war north to deny Japan access to America through the Aleutians, and they didn’t have enough white soldiers to build the road. Reluctantly they sent black soldiers, kept them away from white people and reporters, hid them in the deep woods. The white soldiers got all the credit for the epic achievement.

Our series corrects that—immerses you in the black soldiers’ experience.

We wrote about privates and sergeants, not colonels and generals. We wrote about how it felt to be them in that time and that place. We wrote about their misery, their fear, their patriotism and their triumph. We wanted our readers to live the adventure of these ordinary men who stepped up and built the extraordinary Alaska Highway.

And we wanted our readers to know about the black soldiers who became ghosts in history, gave their all for a country that couldn’t bring itself to thank them or even remember them.

You can also get the books on Barnes and Noble, Kobo, Apple Books and at your local bookstore.

Glacier Route to the Yukon

Glacier route? Not really. When, in 1898, men and women headed for the Yukon came to the Valdez Glacier they came in ignorance. Some left it a lot more educated. Some never left it at all.

You hear that gold in some place called the Klondike is making men filthy rich. You want very much to be in the Klondike. You get helpful advice about paths to the gold fields. You haven’t learned yet that hustlers offering helpful advice are just about the only people really making money from the Klondike Gold Rush.

You hear that the shortest, easiest path to the Klondike gold fields is the glacier route through Alaska. Just pack up your food and your gear, load it on a ship, sail up from Seattle to Valdez, Alaska. From there, head north on the most direct route to Eagle on the Yukon River. A short hop over the Canadian border on the river and, bingo, you’re there. The Klondike.

In Seattle you book passage for Valdez, and you have smooth sailing until your ship crosses the Gulf of Alaska. There the sky alternates snow and sleet, and gale force winds stir up the waves, tossing the ship like a cork.

And Valdez doesn’t really exist—you and your fellow rushers are in the process of creating it. The ship drops you and your gear onto an icy mud flat fronting the Valdez Glacier. Surrounded by 500 fellow immigrants, knowing more ships and more immigrants are coming right behind, you gather it into a pile.

You get a six-foot sled, load it with 200 pounds of gear, harness yourself to it and drag it five miles to the foot of the glacier. After several trips you have it all at the foot of the glacier. You aren’t even started yet. From sea level the glacier climbs in “benches” to its summit a mile up in the air. After two weeks you find yourself at the 3rd bench of the glacier rigging a windlass to lift your gear up onto it.

Around you men die. Some fall into deep crevasses. Some die from over-exertion. Behind you avalanches bury not individual men but parties—groups of men.

Three weeks from the icy beach the shipping companies call Valdez you are at the fourth bench—3,660 feet. And a week later you reach the mile-high summit.

When you get to sit for a moment you try to remember who sold you on the Valdez Glacier route to the Klondike.

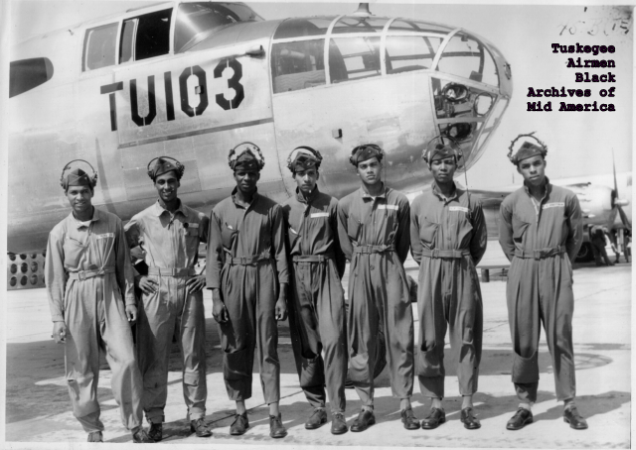

Tuskegee Airmen and Pvt. Thad Bryson

The Tuskegee Airmen, a segregated unit of black pilots, commanded by Major Benjamin O. Davis, one of that rarest of beings in the WWII Army, a black officer, came, early in 1942, to Eglin Field in Florida.

And they came to Private Thad Bryson.

Thad had known little beyond his black community in Old Fort, North Carolina. He lived in a two-room house on a small farm. Nobody in North Carolina expected much from a young black man, and it didn’t occur to young Thad to expect much from himself. He vaguely knew a bigger world existed, but a young black man from the Carolinas didn’t expect to experience it.

WWII changed that expectation profoundly. He spent most of 1942, struggling through Alaska with Company B of the 97th Engineers, helping to build the Alaska Highway. But before he got near the frigid Alaska wilderness, Thad had the first Army experience that changed his expectations, his attitude and the trajectory, not only of his life, but of that of generations to come. It’s important for you to know that we heard Thad’s story from his son, Fred. And that Fred spent his life as a college professor.

More on Young Black Soldiers of the 97th

Very early in 1942, just before the Corps of Engineers dispatched them to Alaska, the segregated 97th built roads and runways at Eglin Field. Thad cooked in the mess hall. When the 99th Pursuit Squadron of the Army Air Corps—the Tuskegee Airmen–came to sharpen their bombing skills on Eglin’s practice ranges. They ate in Thad’s mess hall.

Thoroughly impressive young black men, the Airmen flew airplanes! They had been to college! And they talked “educated”. It had never occurred to Thad that black men could do those things. Was it possible he could do those things?

One day a young white lieutenant walked past Major Davis in the mess hall. In the Army lieutenants passing majors salute them, but the white lieutenant failed to render that courtesy to the black major. Thad watched, open mouthed, as Major Davis halted the lieutenant, called him to attention, and sternly collected the required gesture of respect.

When the lieutenant moved on, Thad came to rigid attention, rendered his own salute. The major returned it, smiled ever so slightly–and winked.

Doctor Stotts, Deep Woods Surgeon

Doctor Stotts, forced to do surgery in the deep woods, cut through his patient’s scalp behind his left ear with a razor blade; drilled a triangle of three holes with a wood brace and a 3/8 inch bit; cut between the holes with a hacksaw blade removed the ‘plug’ and removed a clot. Not a normal surgical procedure—except on the Alaska Highway Project.

The doctors available when soldiers got hurt on the Alaska Highway Project had to be good—and creative. The soldiers worked a dangerous job, deep in the wilderness. The Far North woods didn’t offer a lot of medical facilities. A story from Chester Russel’s Tales of a Catskinner offers what might be the most extreme example.

A trailblazing crew, including a soldier named Moore, happened to be following a D8 as it powered into the trees. A tree limb broke loose, flew back over the top of the dozer and struck Moore on the head. He fell to the ground, unconscious.

A medical corps doctor named Stotts, made his way to the scene; evaluated Moore’s condition. “There is no way that we can get him out of here in time to save him . . . we can operate here.” Stotts commenced the procedure described above.

Placing the soldier on a cot and erecting a tent over him, the soldiers left him in Stotts’ care and returned to work.

Four days on, Doctor Stotts found Moore’s lungs filling with fluid; sucked the fluid out with a rigged-up air compressor. Several days after that, Chester Russel visited Moore; found him sitting up and feeling pretty good.

The story could have had a better end…

Finally evacuated by air to a Seattle hospital, Moore died in route. Russel doesn’t enlighten us as to what caused the sudden change for the worse. Probably pressure changes as the airplane gained altitude affected the delicate tissues in his brain.

Fighting Water, Building Alaska Highway in Alaska

Fighting water came next for the soldiers of the 97th coming out of Valdez to the Alaska Highway. Soldiers driving dozers and trucks negotiated the narrow dirt road and the breathtaking cliffs of Keystone Canyon. Beyond the Canyon they passed through the narrow walls of packed snow that choked Thompson Pass.

Link to another story “Suddenly Climbing”

Out of Thompson Pass, the existing road they traveled descended past the Worthington Glacier and the glacier’s surging melt water had, as it did nearly every spring, washed out some of the old timber bridges. The process of fighting water began as the Alaska Road Commission rushed to replace them.’

But even intact bridges couldn’t support the heavy loads the 97th brought up the Highway. When heavy trucks and then bulldozers came, the soldiers had to bypass the bridges and ford the rushing water.

Roaring white water, sometimes shallow, sometimes deep, changing depth abruptly, always frigid, cascaded through the streambed. A catskinner would carefully work his roaring dozer down the bank and out into the water, aiming upstream at an angle, knowing the current would push him downstream. Sometimes he made it to the other bank. Other times the dozer sank into the muddy bottom or simply “drowned” and went silent when the water reached the engine. Then the catskinner sat, trapped, on his steel seat in mid-stream while his buddies figured out how to tow him out. The troops got creative with tow cables, trees and other dozers.