The soldiers, black and white, in bivouac through the North Country wilderness building the Alaska Highway in 1942 achieved something epic, accomplished something nearly impossible. But to do that they first had to live there.

For More on the Need for the Highway

For More Highway History and a Map

Bivouacs moved frequently, following the work, so tents, usually tied to trees, scattered informally. Army field manual descriptions rarely applied—except in the case of latrines. Troops located and prepared these critical facilities–twelve feet long, eighteen inches wide and six feet deep—with care.

Officers didn’t perform their most basic and personal biological functions in the presence of mere enlisted men. Whites didn’t poop alongside blacks. For the segregated regiments this amounted to double coverage.

A company bivouac featured a headquarters tent– for the commander, his first sergeant and clerk–along with a mess hall and kitchen tent and numerous five man sleeping tents for the men.

Regimental headquarters and the H&S Company travelled with generators. Company bivouacs made do with lanterns. The orderly room might have one. The mess tent, larger, might have five. The supply tent would have one. And officer’s tents would have one apiece. Enlisted men undressed, slept and dressed in the dark.

The lanterns used cloth mantles – always in short supply. At least one Company Commander got his dad to ship him a dozen every month from down in the states.

The Corps fed its troops. But not well. Few of the men who worked on the highway remembered the food with pleasure. The mess section also supplied its company with water from streams and lakes, purifying it with chlorine tablets. Mortimer Squires remembered containers labelled “White” and “Black”…

A typical kitchen tent came equipped with four white gas ranges and a fifty-five-gallon galvanized “dishwasher”. A large open tub, the dishwasher used a submersible heater which, given enough time, heated the water so men could come by and clean their mess kits. Joseph Prejean who worked in one of those kitchens remembered having to start the white gas burner by throwing gas on it.

The Corps of Engineers didn’t have to answer to OSHA.

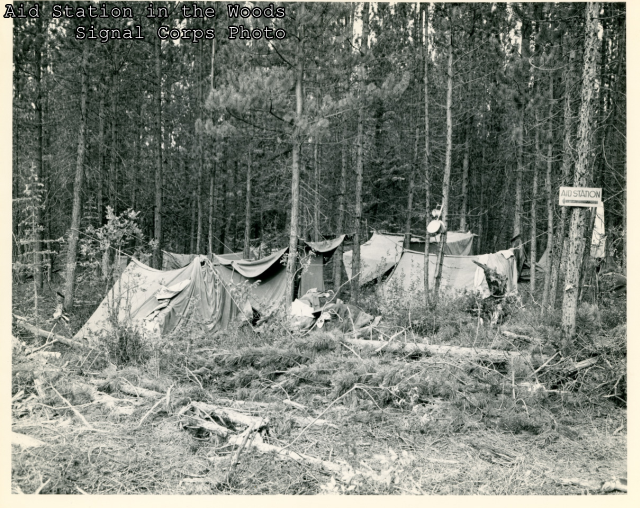

Soldiers got hurt and they got sick, so aid men and, occasionally, even doctors and dentists accompanied companies into the field. Aid stations and dispensaries operated out of tents at the bivouac.

And soldiers get paid, even in the North Country wilderness, and this responsibility fell to the Company Commander. Privates received $21.00 to $28.00 per month, PFC’s $32.00 per month, Corporals $42.00, Sergeants $56.00, Staff Sergeants $76.00, Tech Sergeants $110.00 and a First Sergeant $150.00 per month. The commander picked up and distributed cash pay for the whole company.