Communicable diseases swept the native population of Northern Canada in 1942. And, when illnesses began to appear, the army and civilian physicians who came with the Corps offered their services. At first Canadian bureaucracy made that difficult. Territorial authorities, protecting existing private medical practices, required Canadian licensure for physicians treating Canadian citizens.

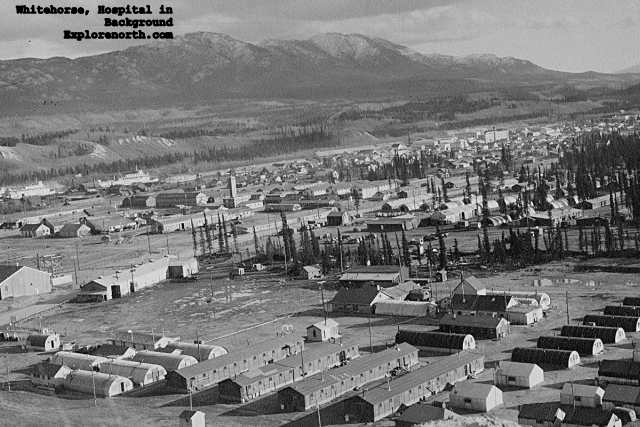

As illness spread, though, and the death count rose, this requirement languished. The Whitehorse Army Hospital provided services to Canadian civilians—except for those with tuberculosis (TB). Not equipped to handle TB isolation, the medics feared they would do more harm than good by increasing the spread of that disease.

In the spring of 1942, Lower Post claimed a population of 150. Influenza killed fifteen of them.

Carcross, the crossroads for the Corps in Yukon Territory, suffered epidemics of chicken pox, measles, whooping cough, jaundice and dysentery. Millie Jones remembered the RCMP piling her and her friends into a truck and delivering them to the Army dispensary for immunizations. The immunizations helped Carcross avoid an epidemic of diphtheria.

Ida Calmegane, 14 when the soldiers came to Yukon in 1942, remembered the epidemics in Carcross. Her mother, a nurse, spent night after night sitting with sick neighbors. One woman lost her husband and two children within hours of each other. And Ida lost her sister.