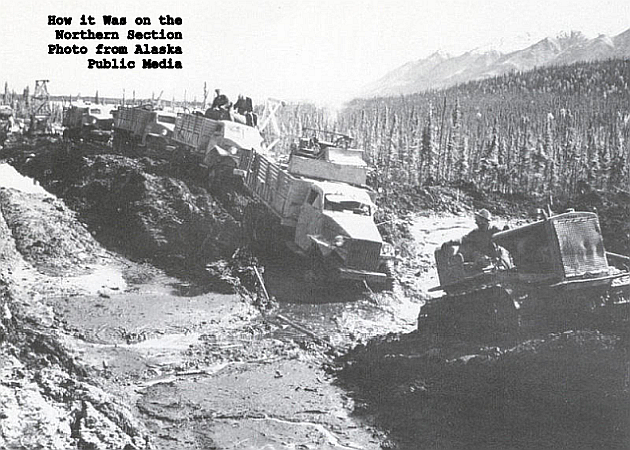

Essential soldiers in a stream of trucks arrived at the Slana sand hills. And now equally essential heavy equipment, especially bulldozers began unloading at the Valdez dock. Before the soldiers could start building road, that equipment had to get to Slana. To men operating bulldozers, the trip from Valdez out to Slana presented a whole new set of problems.

A heavy bulldozer, sometimes towing a grader, rumbled over the still muddy Richardson at a stately four miles an hour, past the quickly emptying 13-mile camp, past Wortman’s and into Keystone Canyon. And, entering Keystone, its young black “catskinner” found himself in a different world.

Towering rock cliffs punctuated at intervals by cascading waterfalls, Bridal Veil and Horsetail, closed in on him from both sides. His skinny dirt passage, cut into the cliff on his left, climbed; and, as he climbed with it, the cliff fell away on his right, a precipitous drop that went from hundreds of feet to thousands of feet. Periodic ruts and washouts narrowed the road to barely more than the width of his dozer and his right-side tracks ground over crumbling dirt right at the edge of the cliff.

At the top of his climb the tractor rumbled through Thompson pass. The civilians of the Alaska Road Commission and the soldiers of Company E had cleared a path through the pass, but snow still towered four stories high on both sides of the road. Occasionally a piece of the snowbank would collapse into the path, blocking it for a few hours while soldiers and civilians scrambled to clear it.

Beyond the pass the road descended past the Worthington Glacier and the glacier’s surging melt water had washed out some of the old timber bridges. The Alaska Road Commission rushed to replace them. But even intact bridges couldn’t support the most essential 23-ton bulldozers. With the heaviest loads, the soldiers had to bypass the bridges and ford the rushing water.

Glacial melt swelled the streams, filled them to their banks and sometimes over their banks. The rushing water, sometimes shallow, sometimes deep, changing depth abruptly, always frigid, rolled through a streambed with enormous power.

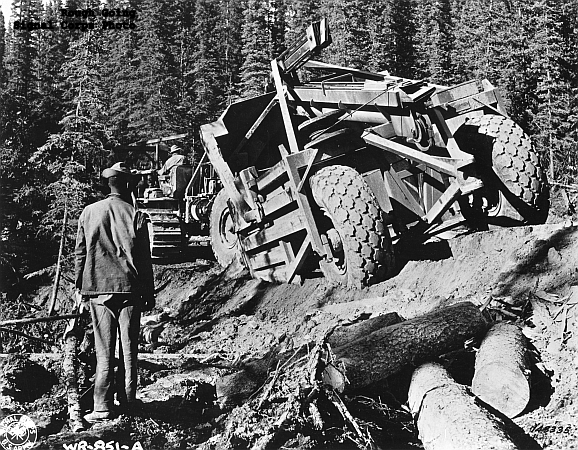

A catskinner would carefully work his roaring dozer down the bank and out into the water, aiming upstream at an angle, knowing the current would push him downstream. Sometimes he made it to the other bank. Other times the dozer sank into the muddy bottom or simply “drowned” and went silent when the water reached the engine. Then the catskinner sat, trapped, on his steel seat in mid-stream while his buddies figured out how to tow him out. The troops got creative with tow cables, trees and other dozers.

More on the Richardson Highway