SS Nisutlin and its Canadian crew forced the Yukon and Teslin Rivers to transport men and equipment for the 340th Engineers.

General Hoge had ordered the 340th to build highway from Teslin through Yukon toward British Columbia. On the other side of the Continental Divide they would meet the 35th Engineers coming the other way. To do that the 340th had to get to Morley Bay–a long, long way from Skagway where, in early May, the regiment cooled its heels.

A bit more than half the regiment waited for the segregated 93rd to build them a road. The WP&YR would carry the rest of the men and, if it ever got up the Inside Passage, the regiment’s heavy equipment to Whitehorse. At Whitehorse they would transfer to river boats, travel down the Yukon River the up the Teslin River and over Teslin Lake to Morley Bay.

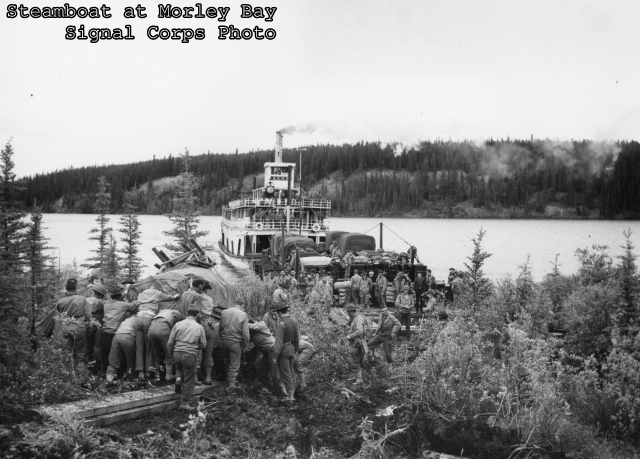

The Yukon River’s ice cleared on May 22 and some 600 soldiers of the 340th lined up by platoon and company to board the trains of the WP&YR and invade Yukon. They scattered of course, the train couldn’t carry them all at once. But around midnight on May 26 the first of them boarded the SS Nisutlin and departed for Morley Bay.

The Nisutlin carried them 240 miles, and one of them, Leonard Cox, remembered the trip vividly. He and his fellows spent five days hanging out on the boat, enjoying the ride and the scenery. “The crew,” Cox remembered, “treated us like kings.”

The Nisutlin generated steam with a wood fired boiler; made repeated stops at native run wood camps along the way. Downstream on the Yukon became upstream on the Teslin and the swollen river went head to head with the boilers. When the way narrowed, sometimes to as little as 100 feet, the river surged at the boat and the boilers lost the battle. Forward progress came to a halt.

When this happened, the captain would maneuver close to the bank. Men would jump to shore, pull a cable across and tie it to a tree. An on-board winch would wind in the cable, drag the boat a few feet. The crew on board would drop anchor. Men on shore would move the cable to a tree just a little further along and the winch would wind up a few more feet. The Nisutlin moved upstream a few excruciating feet at a time until the river widened and the current slowed.

The soldier passengers, according to Leonard, had it “pretty soft”. They relaxed, played cards, and enjoyed meals served on tables covered with white table cloths.

I wonder if people had more patience back in the day? How much longer did that trip take, moving at such a slow pace?