Larkins, the name stood out in the roll of soldiers in the 93rd. Leonard Larkins’ son found us through our research site, contacted us and in short order we headed off to New Orleans to meet his dad. Leonard had served with the 93rd Engineering Regiment on the Alaska Highway in 1942. Our Research Site

We have gathered in a large and comfortable room. On a big screen TV in front of us, Researcher Chris cycles through photos from the Highway. Mr. Larkins and I sit slightly apart and I struggle a bit to hear his quiet voice.

I tell him about interviewing Millie Jones in Carcross; tell him that 8-year-old Millie and her schoolmates had rushed, excited and thrilled, to the depot when the first soldiers arrived. That makes him grin.

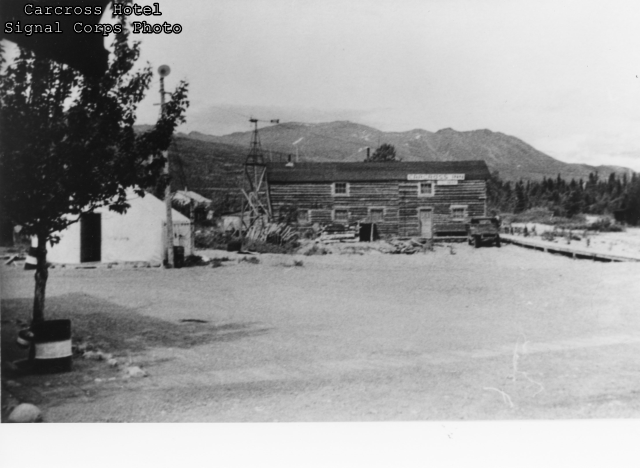

The people in Carcross didn’t understand what race meant to the Americans. Didn’t understand why black soldiers couldn’t come into the hotel. But they came to the back door for water, and the cook, Millie’s mom, would sometimes hand out bread and cookies. Smiling and nodding, Leonard remembers, confirms that.

I tell him Millie’s story about the soldier who, spotting a piano, sat down and banged out “Pistol Packin’ Momma”. He laughs, delighted. Doesn’t remember that, but the story clearly rings true.

He also confirms that the men often sang spirituals while they worked. His sons and I, remembering marching and counting cadence during our days in the Army, try to convince him that’s what he remembers. It’s not. The men sang just like they did in the fields of the plantation back home. He seems surprised that we are surprised.

Out on the road, desperate to make progress, the Corps needed heavy equipment, especially the big D-8 bulldozers. Leonard volunteers that it took a long time to get equipment; confirms that when equipment finally came up to Carcross, they had the devil’s own time getting it through the woods to the road.

Link to another story “Carcross Met the Black Soldiers”

“They turned over easy. Two guys died.”

Chris puts up a photo from the road; a muddy gash through a hill, covered with slash and fallen trees, black soldiers working with axes and shovels to clear it up. Leonard Larkins reacts strongly. “That’s what I did.”

One of his sons asks about his specialty. He struggles to answer—didn’t have one. He painted numbers on mileposts, shoveled, swung an axe, dragged brush. He wrapped TNT in the form of primacord around difficult trees—to explode and drop them. His sons hadn’t heard about that. We hadn’t either.

He has a vague memory of crossing a big river on a ferry. That would have been the Tagish River. I mention Big Devil’s Swamp—Company B losing a bulldozer forever, deep in the muskeg. He grins, remembering hearing about that. “That was a bad place.”

The 93rd’s most heroic moments came when Company A made a last desperate dash to the Teslin River with the white 340th hot on their heels. Company A built the last 20 miles in just six days, and men from the two regiments reached the river together.

I ask him about that last 20 miles, and the question puzzles him. I describe the six days virtually without food or sleep, the white soldiers coming up with them and boarding boats… That he remembers.