Lead, follow or get out of the way. The first weeks in March 1942, before work on the Alaska Highway even started, set the tone for the whole eight-month project. March saw the enormous effort to get the Corps’ juggernaut in place and making road. Some of the regiments in that juggernaut didn’t even exist on March 1, and no soldier engineers had come anywhere near the subarctic north.

The ‘very highest authority’ had ordered the Corps to build the highway and do it immediately, and the Corps had leaped into action. The Corps built things fast under difficult circumstances. They existed for that purpose.

Link to another story “Wartime Government in Action”

Asked for a plan, General C. L. Sturdevant had submitted one in two days, knowing as he did so, that it was at best an outline of a plan. Even as he wrote it, he set the bureaucratic machinery of the Corps in motion.

He had already made his most important choice–his commander on the ground, the man in the lead, would be Colonel William Hoge. From 1935 through 1937 Hoge, a West Pointer with an advanced engineering degree from MIT, had commanded the 14th Engineers in the construction of the Bataan Highway through the Philippine jungles, reporting directly to Sturdevant.

The two men met on 12 February 1942 to consider their most urgent task—turning Sturdevant’s outline into a real plan. Because they were both Army Engineers, they understood one thing that civilian engineers would have considered absurd—they did not have the luxury of time to complete the plan before they started to implement it.

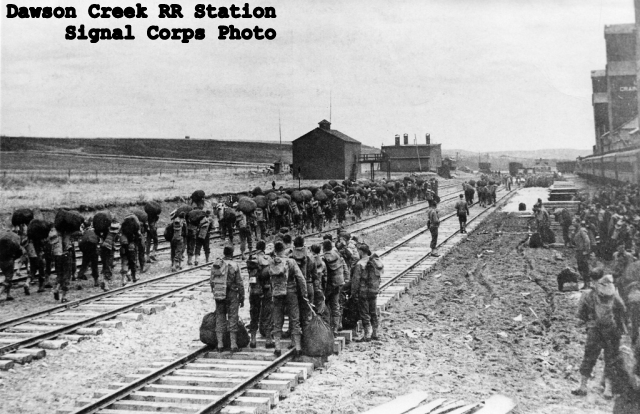

A week after that February 12 meeting, Colonel Hoge’s boots were “on the ground” in Edmonton. With him were Fred Capes, a construction engineer from the Public Roads Administration (PRA); Lt. Col. Edward Mueller of the Quartermaster Corps; and Lt. Col. Robert Ingalls, Commander of the 35th Engineering Regiment. Twenty-four hours later they climbed off a train in Dawson Creek, British Columbia to meet Homer Keith, the Canadian assigned to ‘liase’ with them.