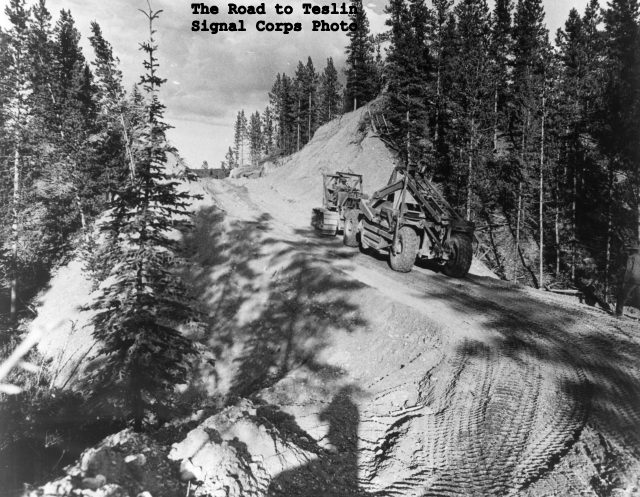

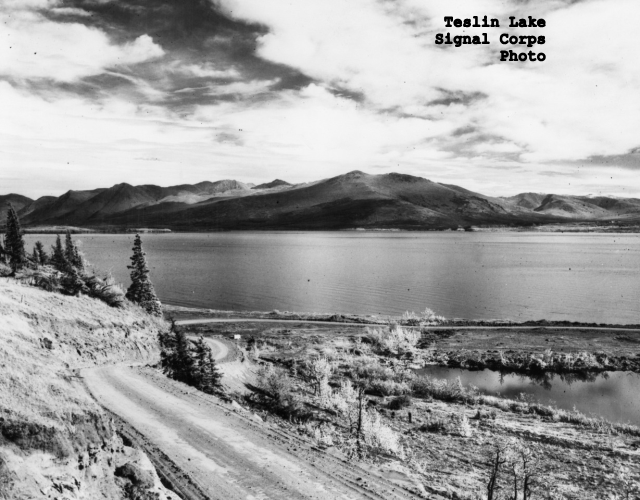

Tiny Teslin Post never saw it coming. In July 1942, the soldiers of the 93rd Engineers, with their bulldozers and trucks and graders suddenly roared out of the woods beside Teslin Lake. The soldiers bulldozed at and around the tiny village and its 130 citizens, dropping trees in every direction.

Link to another post “Climax at the Teslin River”

The soldiers had built Alaska Highway south along the east shore of Teslin Lake to where the Nisutlin River forms into a bay that runs into the lake—at Teslin Post. The soldiers would build their Highway right through tiny Teslin, ferry across Nisutlin Bay and keep going.

The citizens of Teslin didn’t know what to make of it. Excited by the sudden appearance of hundreds of soldiers bulldozing at and around them through the woods, they marveled at the transformed landscape. But Captain Boyd of the 93rd in his memoir Me and Company C, recalled that they also recoiled from “hordes of men, overturned trees, mud strips and massive machinery churning through bush land…”

When the bulldozers pushed through to Fox Point and roared into Teslin, little Dolly Porter hid in panic from the massive machines pitching trees in every direction through her world. Tom (Bosum) Smith remembered that the rumbling power of the dozers disturbed and upset the adults in his village.

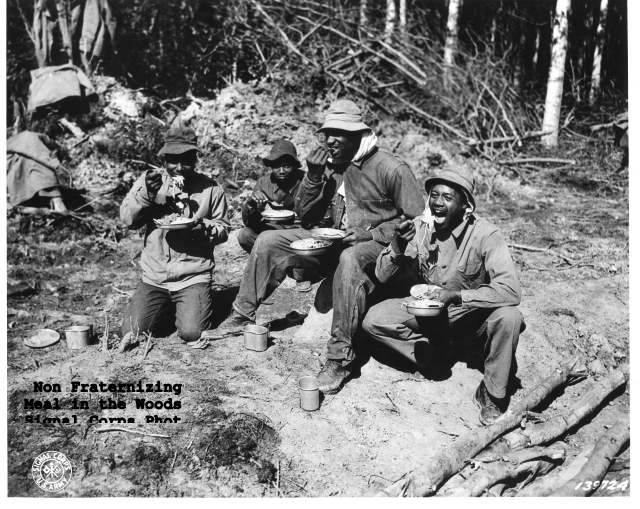

All the same, a few curious, and brave, Teslin people tried to walk the road or even hitch rides. The Army had issued strict orders to the black soldiers not to mingle, but they couldn’t keep the citizens from gathering in their boats along the lake to keep an eye on progress.

Captain Boyd of Company C remembered a white Scot named McGregor who ran the trading post. He also remembered two officers of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who lived at the “Mountie Station”. McGregor welcomed the black men to his store. Not as accommodating, the RCMP Sergeant ordered him to keep his black soldiers out of the settlement altogether. Boyd complied and instructed his Non-Commissioned officers to keep the citizens away from their bivouac. But he, “was sure there was some commingling of the soldiers and the Indian belles.”

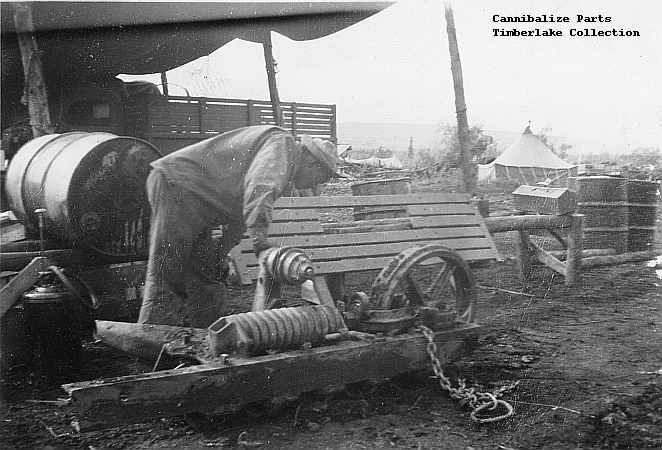

The engineers pressed local river boats into service wherever feasible. The sternwheelers and barges steamed constantly up Teslin Lake delivering equipment, and some villagers in small boats or canoes, traveled down Teslin Lake, to monitor the action.