Send food or send coffins. Regimental Supply received that message from Company F’s commander at the beginning of January. A joke?

Probably.

But the 97th Engineers had endured a truly horrific winter and January threatened to take horrific to a whole new level.

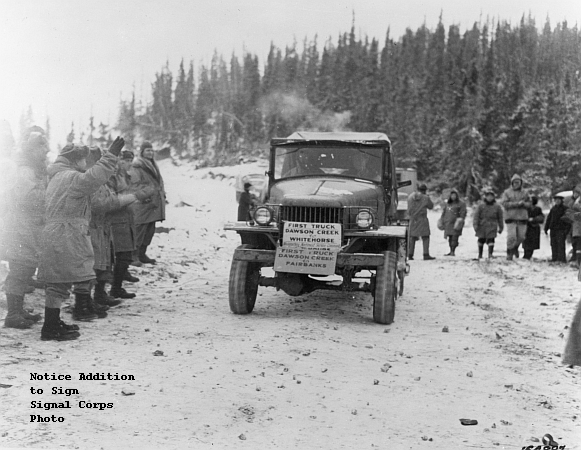

In November, thinking they had a brand-new land route to Alaska, Headquarters intended to use it. Commanding General O’Connor ordered the 97th to scatter all along the Highway through Alaska to keep it open and passable for the Fairbanks Freight.

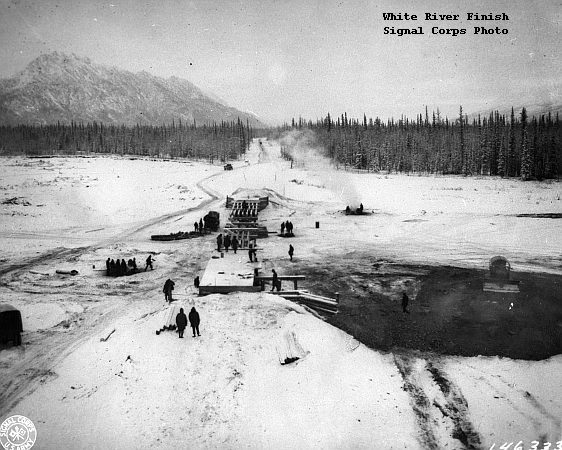

Colonel Robinson dutifully distributed his soldiers along the road from the White River north to Big Delta. But the soldiers on the ground knew the highway from Whitehorse north to Big Delta wouldn’t support the Fairbanks Freight this winter. Snow plugged the road. Ice mushroomed across it. Crude, hastily built bridges collapsed. At the Robertson River, between Tok and Big Delta ice formed seven feet above a bridge already nineteen feet above the streambed.

Worse, the soldiers of the 97th had nowhere to live. Civilian contractors had started building barracks at a few locations, but they departed for the warmth of home in November.

Company A settled at Beaver Creek in November, lived in tents while they built log cabins from scratch. The men labored through November and December during each day’s five or six hours of daylight. When the temperature got colder than forty below, they stopped, “and there were a number of those days.” While they labored, they lived in tents. The cooks prepared meals in a sled mounted cook shed—when regimental supply could send food.

At Northway Company F also started from scratch. By November 13 they had two small buildings and a root cellar.

And the 97th struggled to get supplies. Knowing that Thompson Pass would soon close for the winter, soldiers and civilians had raced to get as much material as possible out from Valdez. In November the pass closed. If something they needed hadn’t made it to Slana by then, it wouldn’t come out from Valdez until spring.

On December 12 Captain Walter Parsons, Company F commander, messaged headquarters, “We have only three days rations… How about sending us something to eat…” On December 15 he followed up, “We will be out of rations tomorrow.” On December 30th he messaged, “We had chili con carne for Christmas, how was yours?

And finally—send food or send coffins.