Hinkel, a Tech 4 catskinner in Company C, bulldozed dirt down the wall of Boyd’s Canyon. He got too close, and his dozer followed the dirt over the edge. He rode his steel mount all the way down to the bottom; and, luckily, the dozer landed on its tracks. Boyd, his company commander, hurriedly clambered down the other side of the canyon; found Hinkel shook up with a bump on his head. “Who told you to drive that dozer over the edge of the bank?”

“Nobody, Sir.”

“Then what are you doing down here?”

“I really don’t know, sir.”

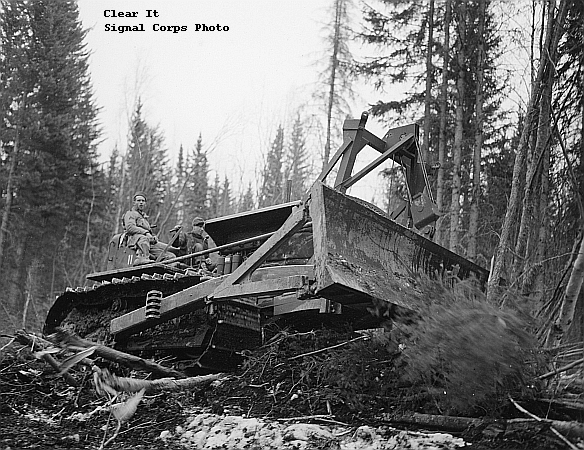

Soldiers built the Alaska Highway through some of the most rugged mountains on the planet. Melting snow and rainwater flowing down from the peaks, had formed into streams and cut channels—some mere dips, others that could only be described as canyons—across the path of their Highway. The soldiers had to bulldoze them full of dirt to level the path.

Problem. Filling a dip or a canyon did not make the stream at its bottom go away. Instead it created a dam. Behind the dam, water would back up, get deeper and deeper until it flowed over the fill, washed it out and recreated the dip or canyon.

They had to accommodate the stream with a culvert, a rough, square tunnel of logs and timbers, then dump their dirt on top of it. The length of a culvert depended on the fill. The sides of the fill had to slope from a wide base to the roadbed on top; the deeper the fill, the wider the base and the longer the culvert.

The men got good at building culverts. An outside contractor noted in his logbook that he had watched, impressed, as a black unit near Teslin built a fifteen-foot-wide and forty-foot-long culvert in forty-five minutes.

Hinkle and Company C did not build and fill the culvert at Boyd’s Canyon in 45 minutes.

In his memoir, Me and Company C, Boyd remembered their effort. Having built an exceptionally long culvert, they needed a very deep fill. To speed things up they had moved Hinkle’s dozer around to the south wall so they could push dirt down from both sides.