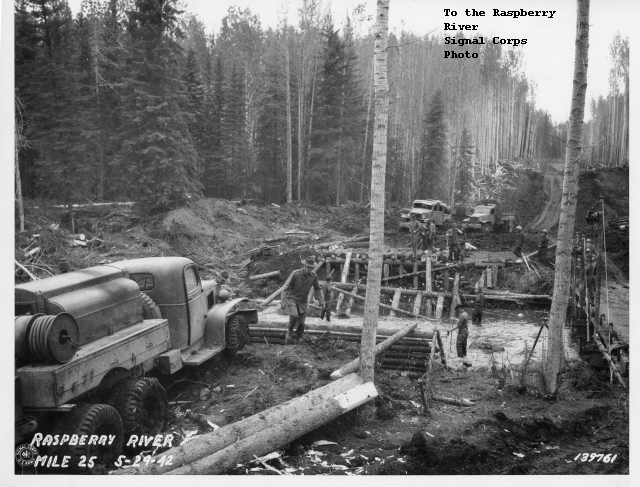

Enlisted soldiers like Chester fought the mud, mountains, cold and mosquitoes; did the actual work of building the Alaska Highway in 1942. The stories that pour from Chester Russell’s memory tell us what it felt like to actually do the epic job.

In the last episode, Chester remembered sleeping in a building at the Liard River camp—the only time that happened during his entire time in Canada. Interviewer Brown responded, “So you were on a year-long… camping trip.”

Chester, “That’s right. (laughs)… Do you ever imagine how stinky them dam sleeping bags was. We didn’t have no laundry up there.” (laughs)

I told you Chester’s stories offered a unique perspective.

Each sleeping bag had two liners. They would sleep in one for awhile then pull it out and sleep in the other. After a few more nights they would turn the first one inside out and sleep in it. You get the idea.

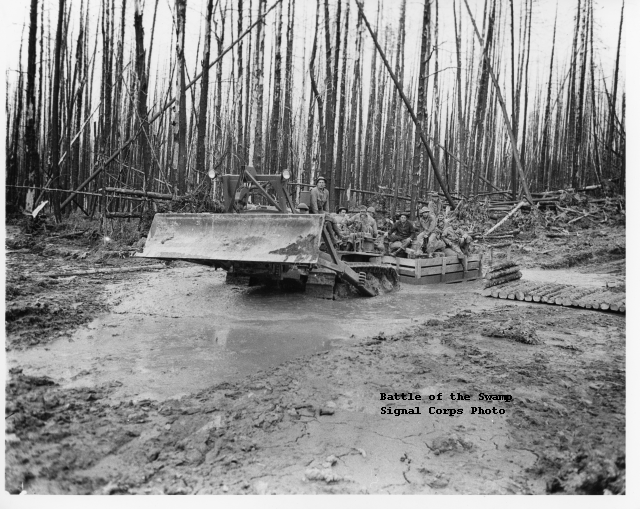

Catskinner Russell remembered the D8 Caterpillar tractor with genuine affection. “…you got up there between the radiator and the dozer blade and you crank [a] starter engine to start the diesel.”

The only problem they dealt with from the eternally reliable “Cats” came from the tracks and rollers. As they plowed through the muddy woods “mud, sticks and stumps and stuff” jammed the tracks. A crew worked alongside the dozers, digging it all out.

Chester came from rodeo, became a D8 operator by accident, and he readily confessed that he and other operators, learning on the job, sorely abused the magnificent machines.

They went through steel cables at an alarming rate. And while they knew to change the oil, they didn’t know other parts needed service too. “…there was some plates up in there that got all froze up and the tractors was burning up oil. A soldier named King turned a blow torch on the mess, “caught the tractor on fire and parts started falling out off it.”

They doused the fire, replaced the parts that fell out; figured out that they needed to remove, clean and replace those parts too.