River ice, the first big problem, confronted Chester Russel and his buddies in the 35th almost immediately as they moved through Dawson Creek and a few miles out to their real destination—Fort St. John.

Just short of Fort St. John, the Peace River loomed. Short periods of early spring warmth softened the river ice. Crossing troops encountered large cracks and the ice undulated and heaved under the weight of a heavy tractor.

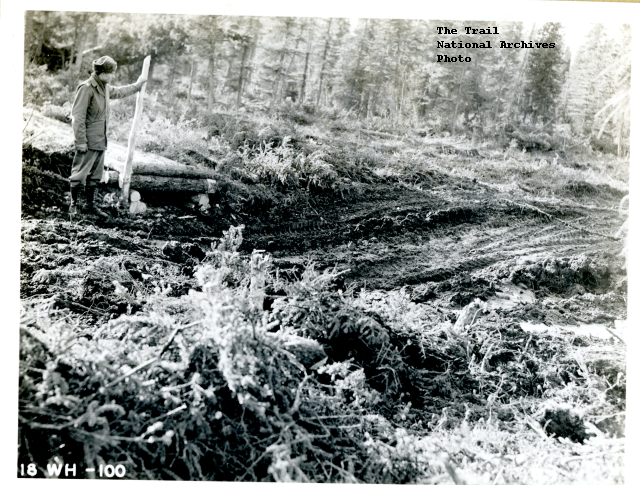

Russell remembered a flatbed carrying an Osgood Shovel down the 10 percent grade to the river. The heavy trailer pushed the tow vehicle sideways and the shovel and the flatbed rolled over into the icy mud along the trail.

Troops collected sawdust and spread it over the frozen river hoping to blanket and insulate the precious ice. Planks over the sawdust kept the tracks and wheels from scattering it. Bundled in frozen parkas, faces frosted and noses blanched white, Chester and the men of the 35th waddled across like a flock of penguins.

At Fort St. John they tried to bivouac. Tent pegs didn’t work in frozen ground. The men lashed the tents to whatever presented itself. They didn’t provide much shelter anyway. And latrines proved impossible to dig. You can imagine how they dealt with that problem.

From Chester’s interview with Earl Brown and Hank Bridgeman in 2003. “Now we got to Dawson Creek and we didn’t slow down. They marched us right through Dawson Creek there, right in… took us to Fort St. John.”

They didn’t stay there long either. The trail to Ft Nelson was dissolving in front of them.