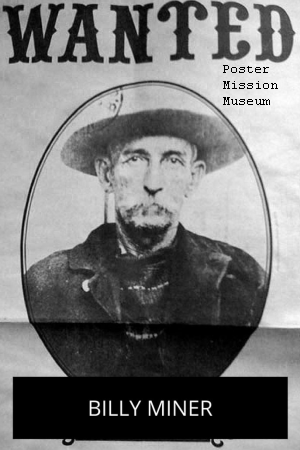

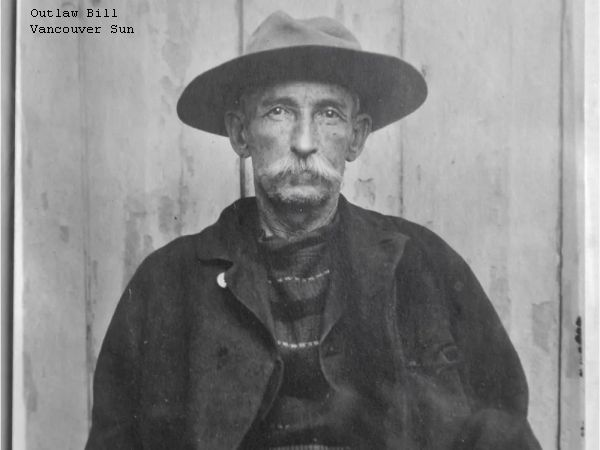

Bill Miner—or “Grey Fox” or ‘Gentleman Robber” or “Gentleman Bandit”—invented the phrase, “Hands up”. A claim to immortality? I would say so.

Link to another story “Sleeping Standing on their Heads”

Born in Michigan he made his way to California and began his sterling career, finding himself in prison three times between 1866 and 1901. Upon his release from San Quentin in 1901, he moved his base of operations north to Canada, and three years later he staged what some historians identify as British Columbia’s first train robbery.

Later, with two accomplices, he thoroughly botched a train robbery near Kamloops—made off with $15 and a bottle of kidney pills. No matter, the robbery inspired a massive manhunt. Caught and convicted because his pocket contained the kidney pills, Miner went to the BC Penitentiary.

Spectators lined the tracks as a train carried him to the penitentiary. The gentleman robber had caught the public imagination. And, more, the Canadian Pacific Railroad had few friends in the population.

Escaping from the BC Penitentiary in 1907, Bill Miner returned to the United States, continued his career, served more prison time, and finally died on a prison farm in Georgia.

In British Columbia, “Gentleman Robber”, remained a celebrity. Drinks, menu items and even pubs carried his name. A song, The Ballad of Bill Miner”—and a 1982 Canadian film, “The Grey Fox”, celebrated his exploits.

Tin Whistle Brewing Company, a microbrewery in Penticton, British Columbia, even produced an ale they called “Hands Up”.