Extreme geography awaited the soldiers of the 93rd Engineers when they left Southern Louisiana in early 1942. From hot and humid Louisiana, they travelled north—way north—to Alaska and Yukon Territory.

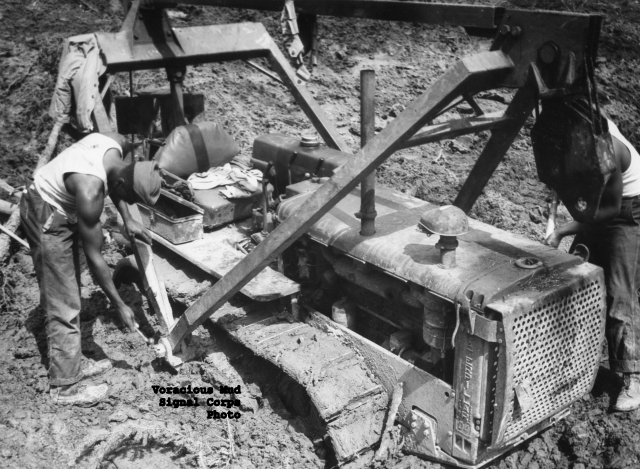

Sergeant Albert France, interviewed long after the fact by Donna Blazer-Bernhardt, remembered their time on the Alaska Highway Project. He remembered hard, challenging work and he remembered living in wilderness camps surrounded by wild animals—bears, wolves, moose. France remembered swamps with mud that literally gobbled up heavy equipment. Cutting trees and digging stumps involved digging down through green grass into a cake of solid ice. They solved that problem with dynamite.

African American, like all the enlisted men in the 93rd, France also remembered the segregation. “The general in charge thought the black soldiers wouldn’t understand what it took to build a highway…”

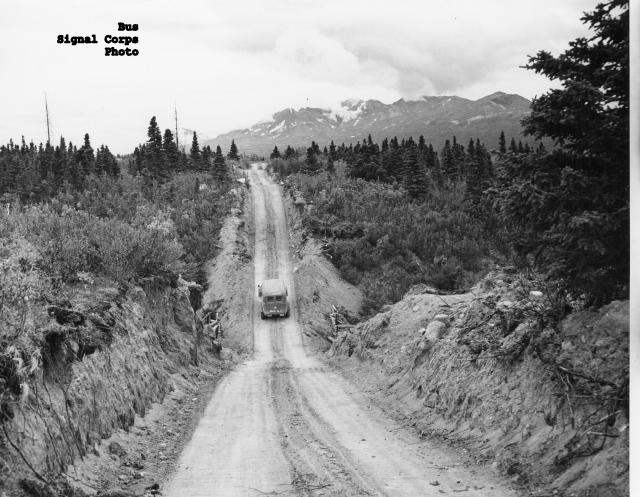

Their work on the road ended in late November and some soldiers of the 93rd worked to build log cabins at Judith Creek. Clyde Deal remembered the blast of an air horn overriding the sounds of hammers and saws one afternoon. Startled soldiers ran to investigate and watched a Greyhound bus move by on its way to Whitehorse.

The road was open! And the extreme geography of the Subarctic included more than Yukon Territory. The 93rd would not winter at Judith Creek.

In December they convoyed back to Carcross and took the train down the mountain to Skagway where they had come in country just eight months earlier. After a short turn to get organized at Chilkoot Barracks. A ship carried them through the wild North Pacific to the Aleutian Islands.

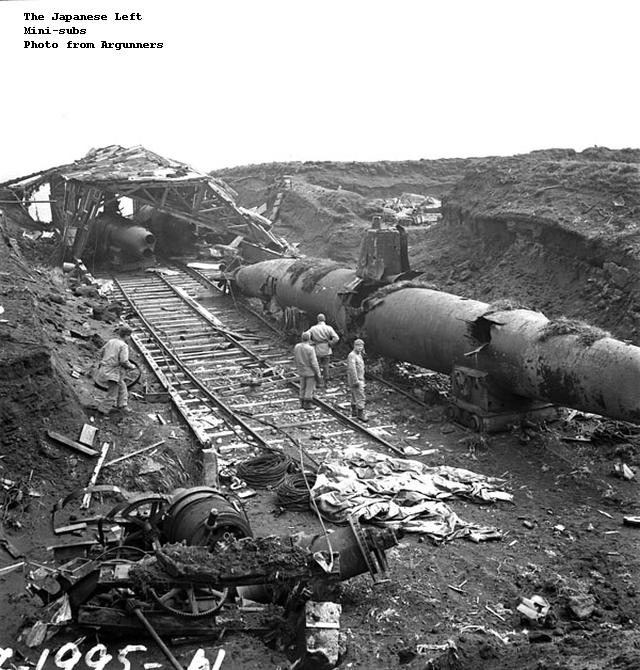

The Japanese threatened the Aleutians and the soldiers of the 93rd would help defend them, enduring the bitter Aleutians weather, to build and maintain airfields on Unmak.

They escaped the Subarctic in 1944 and discovered that extreme geography offered opposites. After a brief stop in Seattle, they headed south through the Pacific to the opposite end of the world, to Burma.

Clyde Deal summed it up. “I’d say the 93rd had the best of extremes… twenty-seven months in the Yukon, Alaska and the Aleutians, followed by eight months in India and Burma.