Women Came to the Klondike Too

The Valdez Glacier looked easy, and in 1897 and 1898 when promoters invited gold rushers to take “The All American Route” to the Klondike, they had yet to learn that hustlers offering helpful advice were just about the only people making money from the Klondike Gold Rush. They came to Valdez and the Valdez Glacier in ignorance. Some left it a lot more educated. Some never left it at all.

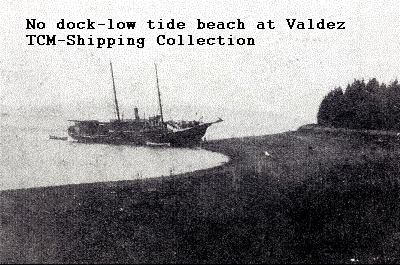

At Seattle expensive gear bothered some. But they headed north to get rich. It took money to make money, right? They packed it up, loaded it on a ship, and sailed up from Seattle through the North Pacific to Valdez, Alaska.

The ships sailed smoothly into the North Pacific, but then they had to cross the Gulf of Alaska. The sky alternated snow and sleet and the wind blew at gale force. The ship rocked and rolled them into prostrate seasickness. And the smell of other people’s seasickness prostrated them more.

Finally. Valdez. Thank God.

Valdez didn’t really exist yet—rushers created it. An icy mud flat fronted the Glacier. The ship’s crew threw gear off onto the ice. Five hundred immigrants at a time, knowing more ships and more immigrants came right behind, gathered their gear into piles.

Each acquired a six-foot sled, loaded it with 200 pounds of gear, harnessed themselves to it and dragged it five miles to the foot of the glacier. Each went back for more… and more… and more until they had it all at the foot of the glacier.

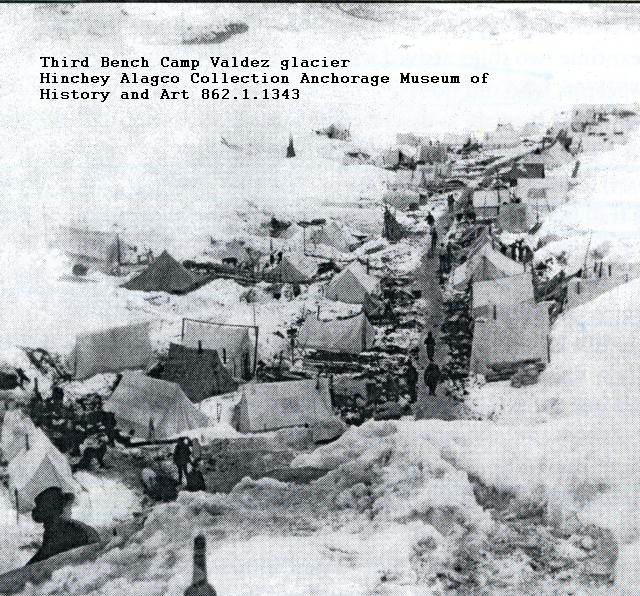

They hadn’t even started yet. From sea level the glacier climbed in “benches” to its summit a mile up in the air.

Two weeks might get some of a “rusher’s stuff up to the third bench. There they had to rig a windlass to lift it onto the bench. People died on the way. Some fell into deep crevasses. Some simply worked too hard and collapsed.

George Hazlett described the exertion. “Think of a man hitching himself up to a sled, putting on 150 pounds and pulling that load from 7:00 am till 2:00 pm, eating frozen bread and beans and drinking snow water for his lunch, then walking back the distance of 10 ½ miles.”

Three weeks out of Valdez the lucky ones reached the fourth bench—3,660 feet. A full month out they reached the mile-high summit. Behind them avalanches buried not individual men but parties—groups of men.

From the summit they had only to cross the rugged mountains of the Alaska wilderness and the Continental Divide—cross it the long way—to Eagle and the Yukon River.