Indians, First Nations, In the North Country

Sickness from outsiders, nothing new to the people of the Great Subarctic North. Outsiders who came to the North Country always brought sickness. The first Nations suffered infectious diseases brought by white missionaries and trappers throughout the 19th century. Myriad bugs and germs rode north in the bodies of Gold Rushers at the end of the century. Few societies on earth developed in an isolation as profound as that of the indigenous societies of the North Country, and that isolation set them up for the recurring bouts with outsider borne diseases.

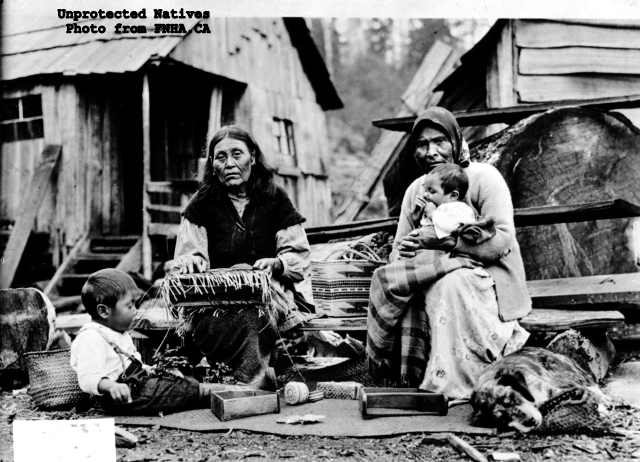

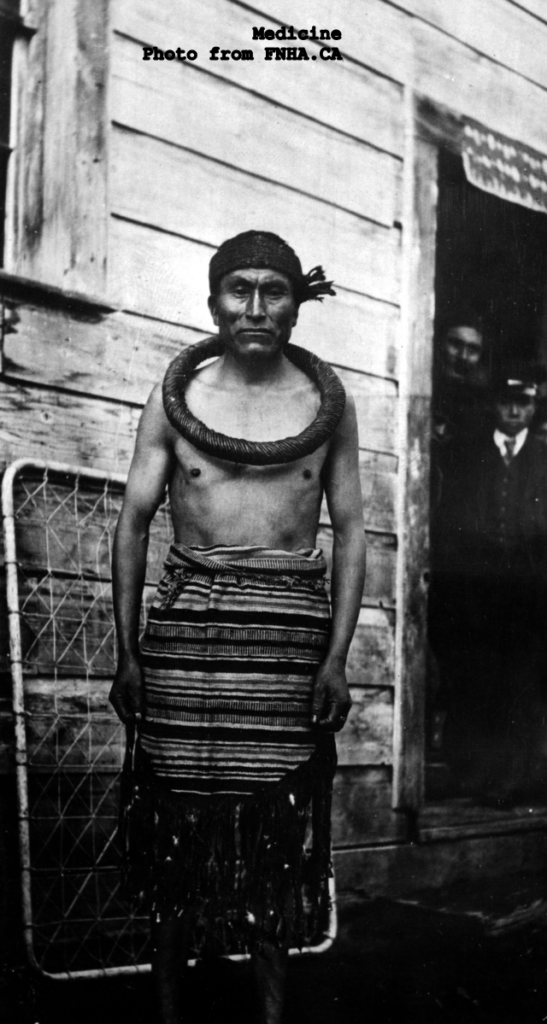

Sickness came, even in isolation, to the Tlingit people and their fellows; but for centuries it had not come often. Household remedies dealt effectively with minor ailments such as rheumatism and upset stomach. When someone fell seriously ill, a relative would carry a gift to the medicine man and he would decide if he could take the case. Medicine men came equipped with animal skins, bones, claws, stones from animal stomachs, medicinal herbs and carved and painted walking sticks.

The victim might lay by the fire under a blanket as the medicine man yelled and shouted for his spirit-helpers and an assistant played the drum. Sometimes he would suck out, or cut open to pull out, whatever evil thing was making the patient sick.

As they travelled or picked berries or ventured out to set snares, everybody gathered medicinal plants. Angela Sidney remembered the tradition of bringing back seeds to scatter near camps or villages–a wild celery, medicine for rheumatism, or balsam fir whose boughs, heated on a fire, relieved toothaches.

The natives’ bodies, never exposed to the diseases of the rest of the world, had no defense when outsiders making their way north unwittingly brought them along. Medicine Men and herbs didn’t offer much defense against tuberculosis—a disease that had become endemic among the First Nations long before the Corps arrived. Pneumonia and bronchitis killed despite the Medicine Man’s best efforts.

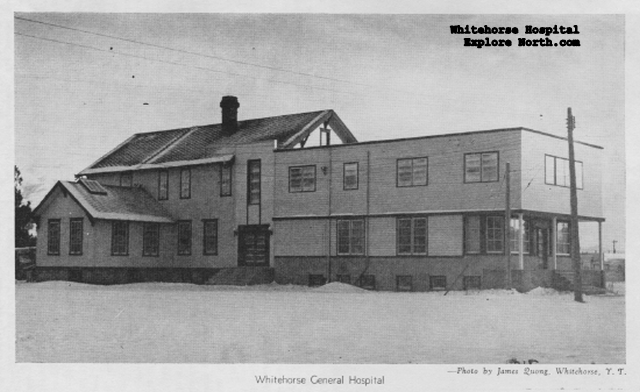

So the Corps of Engineers brought sickness to the North Country. The problem started slowly, gained momentum through the spring and summer; came to the attention of appropriate authorities gradually.

November 2, 1942

Dearest Helen,

…one of the Indian villages they all got measles.

Five people died. Seems they get some kind of trouble

in their head and it kills them…