Schemers and dreamers, over a century and a half, created ways to travel and transport material through the great subarctic North—a few ways. This difficult piece of the world fought back at every turn. But over time a stream of adventurous; brave; inventive; and, above all, greedy schemers came to do battle with it.

The very first schemers in British Columbia came to install wire. Almost as soon as Samuel Morse invented the telegraph, men dreamed of using it to link continents. Dreams morphed into schemes. And schemes almost always morph into competition.

An American subsidiary of Western Union proposed to run telegraph wire from San Francisco through British Columbia, Yukon Territory and Alaska to and under the Bering Strait where Russians could take over and run it on through Siberia to Europe. Another company proposed to simply go under the Atlantic to Europe.

The trans-Atlantic schemers won the race. But the Canada route men labored for two years through short summers and long bitter winters, inland from the Pacific Coast and then north. They left behind, not only a half-completed telegraph line, but also a trail. They departed in 1867.

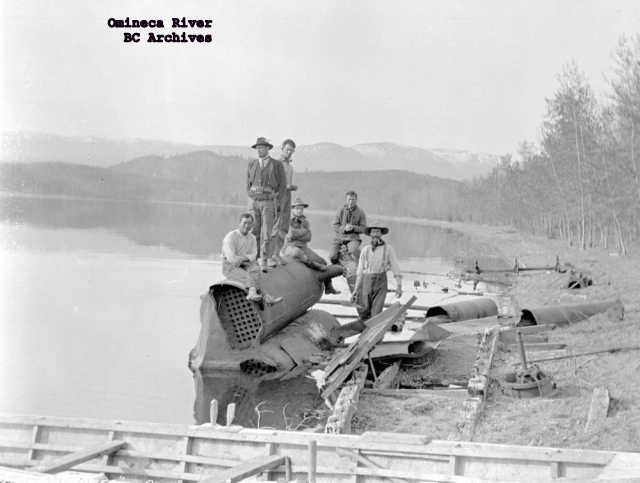

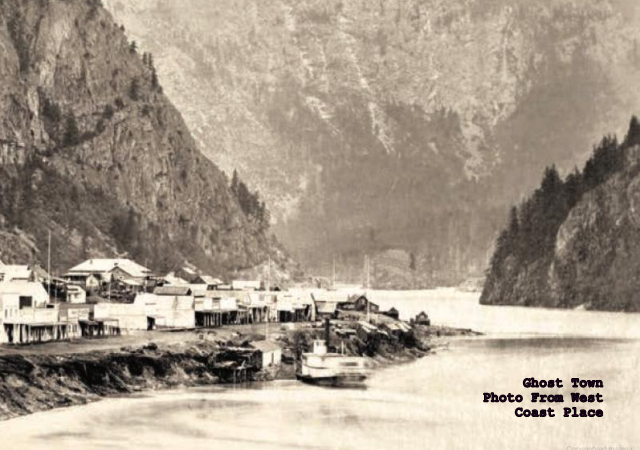

In the early 1870’s a short-lived gold rush inspired another set of schemers to pick up where the telegraph men had left off. They put steamers on a series of lakes, connected the lakes with a series of trails and transported prospectors to the gold fields on the Omineca. When the gold petered out, the schemers disappeared. But they gifted British Columbia with 200 miles of road.

The first prospectors to use the trail rode an old steam sternwheeler up the lakes. The prospectors didn’t find much gold, but they paid their fares to the schemers. And that was the point. The schemers made enough money to replace the old steamer and still make a profit. And that was good because on the way home it simply came apart in one of the lakes.