The United States Army didn’t create racism in the ‘40’s. The United States had struggled with race for 170 years and, in 1942, thoroughgoing racism and vicious discrimination permeated American society and government. The Army and the Corps merely reflected that sad fact. But its racism stained the story of the Epic Alaska Highway Project

A few days ago, I posted about the impact of racism on the experience of the 95th Engineering Regiment in British Columbia in 1942. A sorry bit of history and a difficult post to read—and write. At command levels the racism never went away or even moderated. In the wilderness, though, on the ground experience changed some men for the better.

In the beginning white officers believed—the army trained them to believe—in the myth of black incompetence. They couldn’t trust black men to learn or to think or to solve problems. Nor could they trust them to operate or care for sophisticated equipment.

For their part, most of the black soldiers who worked on the Alcan grew up in the rural south. They had grown up with Jim Crow; and, if the army disappointed and infuriated them, it didn’t surprise them. John Bollin of Company F listened to his tent mates talk at night “about how bad it was back home, how their bosses used to treat them, and they’d tease each other. ‘Your boss treated you worse than my boss.’ This was an accepted way of life.”

Most of the young white officers initially saw the young black men they commanded in terms of stereotype. They expected certain attitudes and behaviors and abilities. If they encountered an attitude or behavior that didn’t fit that was merely the exception that proved the rule.

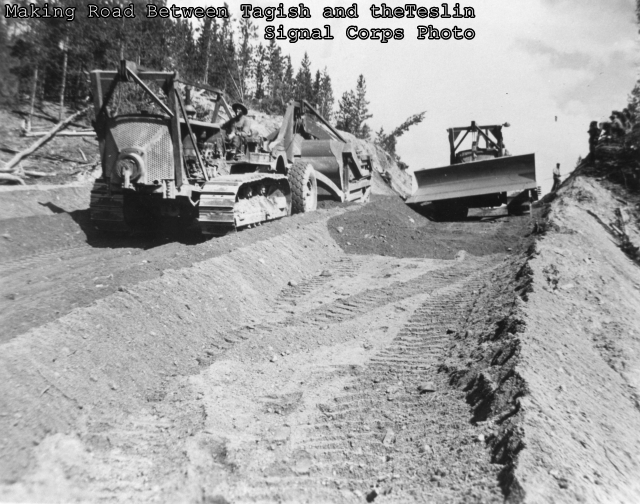

Then the black soldiers came to the road, and the issue of competence and ability got addressed right off the bat. Able black soldiers became competent ones very quickly.

Harold Richardson noticed. Many of the engineers only had “a few minutes” of instruction. “Yet some of the best operator’s, both colored and white, were boys that had never been on construction equipment until they arrived on the project.”

And James Lewis noticed. Few “negro soldiers” brought experience operating heavy equipment with them to the army. “But the Alcan Project gave them experience. They became good equipment operators. And they liked it. A bulldozer was an expensive machine that manipulated and transformed wilderness into road. When a black engineer climbed aboard a D8 tractor, it gave him a sense of personal achievement and importance that ordinary physical labor lacked.”

In Northern Canada and Alaska, the Army put black soldiers and white officers in the same woods. They suffered the cold together. They fought muskeg and mountains together. Mosquitoes turned out to be equal opportunity tormenters.

Men, fighting and enduring together, found it hard to maintain the stereotypes. Some of the young white officers remained racist to the core. But a lot of them didn’t. They came to rely on black soldiers’ skills and the respect the men who owned them.