Colonel Whipple, commander of the 97th in early 1942, understood very clearly that his bosses wanted him to keep his black soldiers away from Alaskans. Once he had his men off the Branch, he focused on getting them out of Valdez. Company E had walked through the snow directly off the dock, out to the Richardson Highway and then 13 miles out of town.

On May 3 Company B walked directly from the ship out to join Company E at the 13-mile camp. But four full companies remained at the airstrip. Alaskans would have to put up with black neighbors for a few more days. Companies C and F, including Sergeant Heard and his nine men, left on May 10. Companies A and D finally left town on May 20. Whipple and his staff, his H&S Company, remained at the airstrip.

Wherever they did it during that first week in Alaska, soldiers had to pitch and then sleep and cook and eat in canvas tents. A company arrived at a bivouac, the company commander showed his four platoon leaders where their tents would go, with his first sergeant he would find a central location for his headquarters, his officers, his kitchen and mess tent. The platoon leaders and sergeants would disperse, taking their men to their assigned area, directing each squad leader to the location of his squad’s ten-man tent.

And the soldiers would go to work. Clear snow away, lay out the canvas, drive pegs through loops into dirt to hold it down. But in April and May Alaska dirt is the consistency of a brick. Some soldiers, more creative, figured out work arounds. A man could tie the canvas to something in place of a peg. The tent would sit crooked, but it would sit. Some gouged holes out of the brick earth, inserted the peg, poured water into the hole and waited for it to freeze.

When time came to eat, the company mess offered little except gray boxes of rations—suspicious concoctions in green cans, cold and coagulated. Fires sprouted, and men figured out how to heat the cans.

Finally came time for exhausted men to go into the tents, climb into their sleeping bags or bedrolls. Sgt Monk remembered, “Your breath would turn to ice inside your blankets at night.” And he remembered his bedding. “I had one blanket. My buddy had one blanket and an army jacket.” The men lay shivering in the dark, trying to sleep and wondering what the hell they had ever done to deserve Alaska.

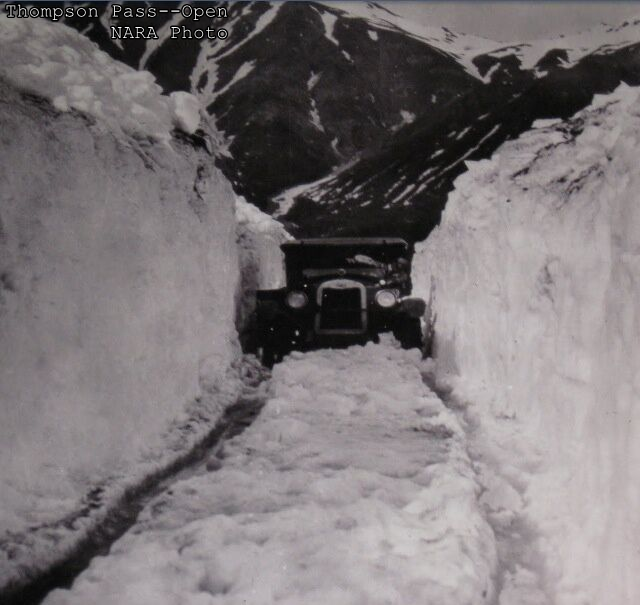

Colonel Whipple continued accumulating problems. He had managed, by May 10 to get four companies out to the 13-mile camp. But neither they or the companies coming behind could go much further. Just six miles on, at Wortmann’s, the Richardson climbed into Keystone Canyon and then Thompson Pass, 2,805 feet above sea level. Thompson Pass averages 46 feet of snow every year; becomes a dangerous place.

As they did every year, the Alaska Highway Commission had closed the pass for the winter. In May they struggled to get the snow out and open it again. The men of Company E moved up to Wortmann’s and pitched in to help, but the effort took time. The first soldiers of the 97th to get over the Pass didn’t do it until May 20.

General Hoge had dispatched Whipple and the 97th to Alaska with a schedule. At the end of May, hopelessly behind, Colonel Whipple didn’t bother to worry about it.