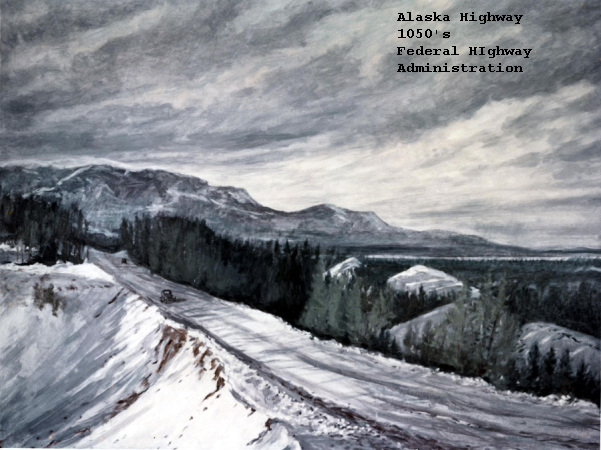

Shirley Balinski commented on one of my posts. “Traveled that road several times, by car, as a kid (mid 1950’s to early 1960’s). We lived homesteading in Alaska. It was an experience! The road was very rough, wild territory, extremely muddy or dusty, swamps to high mountains, mostly gravel or dirt. The “berms” of dirt and logs were still visible along the sides where they had been pushed by the bull dozers.”

I love comments, especially the ones that come from someone who knows things I don’t about the North Country. And I responded immediately. Shirley, you should be writing a blog. I, for one, am fascinated by the tough folks who homestead up there. If you have stories, I will share here and on my blog site.

Shirley responded.

“…Yes, as a kid I lead a very interesting life, many experiences!! Some good and some not so good. I guess that is why I always related to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s adventures in her books. Life was similar. A man, our friend and neighbor, wrote a book about his adventures called “Go North Young Man”. His name was Gordon Stoddard. It is still available on Amazon. In this book, he writes about our community, Anchor Point [near Homer on the Kenai Peninsula]. He talks about our neighbors and there are pictures.

We lived in his home when we arrived until we pushed further back onto our homestead. He also gave us our beloved pet dog, Kiska. He does a much better job than I could ever do! I was born in Alaska before it was a state. My mother, ” brought me out” (to lower 48), when I was 3 months old, to see grandparents! So, many stories, of old, original Alaska, when it truly was a frontier. If you ever see Mr. Stoddard’s book, do not look at the pictures and think, ‘it couldn’t have been that rough. These people don’t look too bad.’ Believe me, it was rough.”

Amazon does, indeed, have Gordon Stoddard’s book, Go North Young Man. He published it in 1957 and in 1961 Pathfinder Books reissued it. I bought and downloaded the eBook, and I’ve just finished reading it. Mr Stoddard makes no claim to be a professional writer, but he’s a very good writer just the same. His memoir fascinated me, and I heartily recommend it to anyone. Most fascinating of all, he writes about Shirley’s family, how he reacted to them and how they came to live in his house. And he writes a lot about Kiska, the dog.