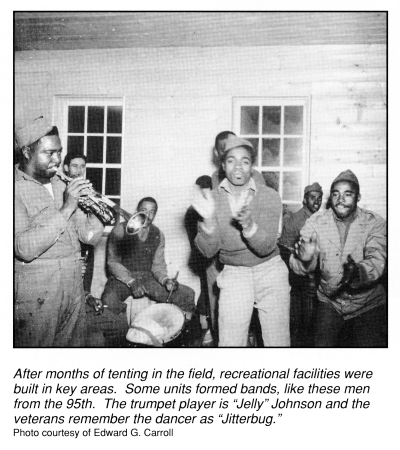

Morale among the black soldiers of the misused and abused 95th Engineers confronted their new commander, Lt. Colonel Heath Twichell, with his biggest problem and he proposed to fix it.

Link to the last story in this series “Pink Mountain and the 95th”

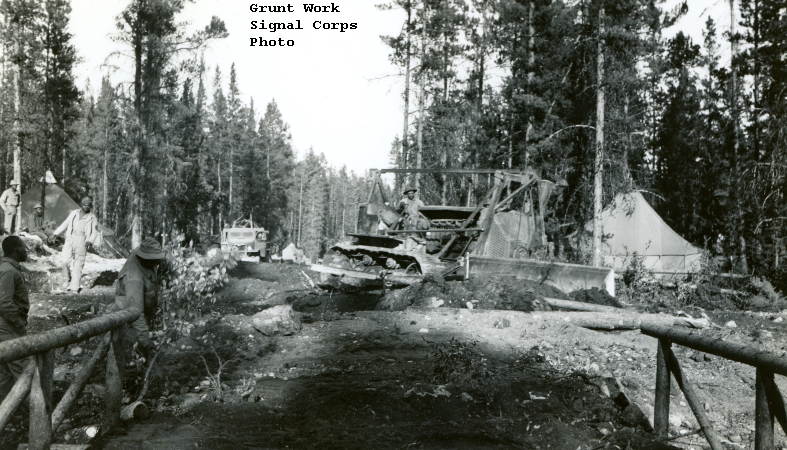

The Army, Twichell knew, considered his new troops substandard; didn’t trust them to operate heavy equipment. He instituted extra training with the heavy equipment he had, and he had operator’s names painted on vehicles and equipment, making clear their responsibility to repair and maintain it.

Should a soldier fall short, his name would be scraped off and replaced with another. Their status in the regiment at stake, the catskinners rose to the challenge. Twichell, Finis Austin, chaplain of the 93rd noted in his book written many years later, encouraged black soldiers to develop ambition and drive and self-respect.

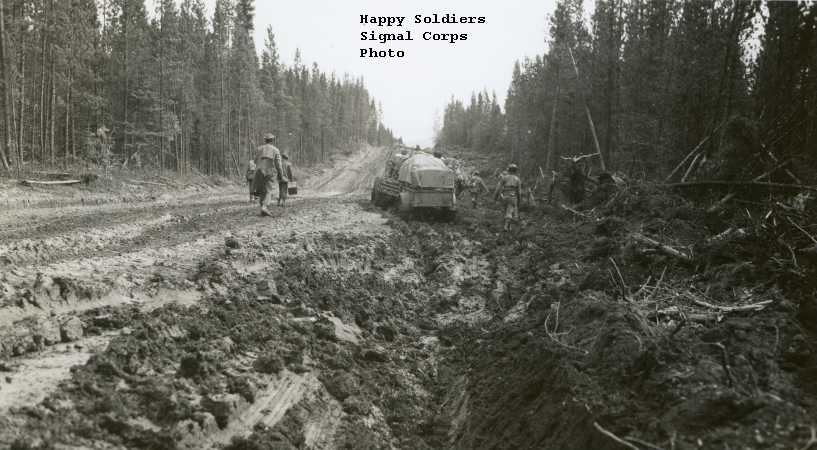

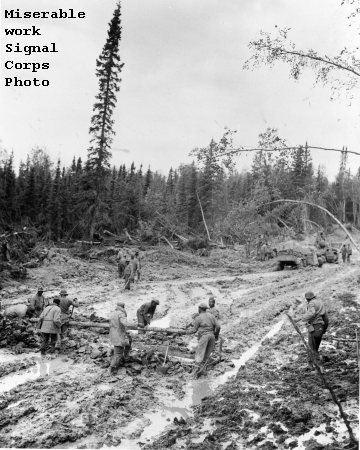

But Twichell needed more, something dramatic. Following the white 341st, the 95th fell “heir to a lot of unglamorous work” Exploring, locating, and clearing, the 341st led the charge. As the road approached the Sikanni Chief River, Twichell saw an opportunity.

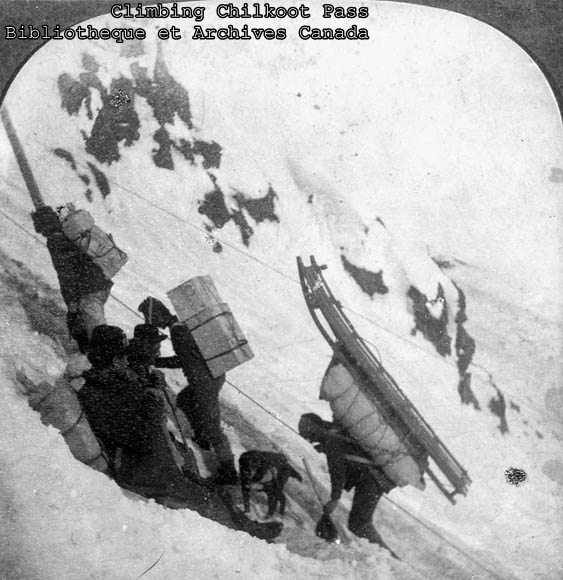

The glacial waters of the Sikanni Chief pour through a canyon between two mountains. The grade down to the river and back up exceeds ten percent. In 1941 a Canadian construction crew working to create a string of airports to Alaska, took three days to get ten sleds of equipment down the last mile to the river. Engineers at their desks in Whitehorse estimated two weeks to bridge the 300-foot-wide river. O’Connor budgeted five days and agreed to give the 95th a shot at building it.

The 341st, of course, had reached the river first. Company A of the 341st dynamited cuts into the treacherous hillside to create approaches. Company B hauled a “seemingly unending number of pontoons” down the steep hill to the shores of the river. On the 20th of July, Company C put a temporary pontoon bridge across the river.

Now Twichell brought his Company A, 166 men, to the site; their mission to build a trestle bridge across in just five days. The commander of Company A, one Lt. Lee, sent two platoons out to serve as point for the effort. Constructing a raft, empty fuel barrels lashed to logs, Sgt. Brawley and Sgt. Price took a platoon to the north side of the river. Sgt. Tucker and Sgt. Bond took another to the south side.

Nervous, Lee had asked Sgt. Brawley, “do you think we can do this in four days?” Excited, Brawley replied, “Yesir, Lieutenant Lee, yesir! We can get it done in four days, you and me.”