Tech 5 Hargoves had no idea, but events in Washington would change his life profoundly. In early 1942, in the near panic that followed Pearl Harbor, FDR and the War Department ordered the Corps of Engineers to create a land route to Alaska—yesterday! At Camp Livingston, Louisiana Tech 5 Hargroves and the other men of the 93rd Engineers knew nothing of this; had no idea of the frantic decisions coming at them down the chain of command.

Link to another story “Leonard Larkins and the 93rd”

Tech 5 Samuel Hargroves wanted very much to go home and marry the love of his life—the lovely Mayola Pleasants. He snagged a furlough and, back home in Henrico County Virginia, on April 7, he did just that.

That very day, the 93 Engineers received orders to prepare for immediate “overseas assignment”. Mayola’s honeymoon lasted three hours.

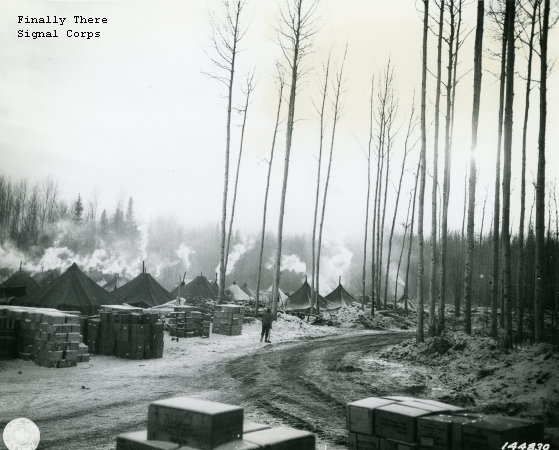

In May, when Company F of the 93rd climbed off the train in Carcross, Yukon, T5 Hargroves climbed with them.

Growing up in Henrico Country, Samuel worked hard and stayed out of trouble. His daughter Shirl explains his good behavior with a big smile. He lost his mother, Courtney, at six and his father, Samuel Sr. at sixteen. When young Sam thought a group of friends might be headed for trouble, he headed the opposite way—he didn’t have parents to bail him out.

The 1940 census found Samuel in Varina, Virginia (Henrico County) working as a farm hand. In 1941 his draft board found him there too. The Army moved him around a bit before dispatching him to Camp Livingston, Louisiana and the brand new 93rd Engineering Battalion. He arrived there in late summer—a few months before Pearl Harbor.

He worked for Staff Sergeant Hezekiah Swanagan in the Company F Motor Pool, didn’t remember anything about the officers except that they were all white except the preacher.

One white First Lieutenant he remembered. “He wasn’t good to nobody. He treated them so bad. Catskinners driving the dozers tried to run over him. The Army moved him out of Company F.”

He remembered, more than anything, the cold. The gas lines froze up on the trucks. They kept them running all night long; put a can of burning gasoline under the differential to warm it up in the morning. He remembered food from cans, not that it was bad but that it froze in his mess kit. On his ship in Skagway harbor, an icicle as big as his arm hung off the hawser. He’d never seen such a thing.

T5 Hargroves served with the 93rd through the Alaska Highway Project and then travelled with them to the Aleutians where they spent the balance of the war building and maintaining airfields.

Back home in Henrico county, Samuel never discussed his time in Yukon and the Aleutians. His daughter, Shirl, knew nothing about any of this until the family threw him a surprise 90th birthday party at her church. That night he talked about being a 21 year old soldier standing guard in dreadful cold.

“We had to go up there and build a road.”