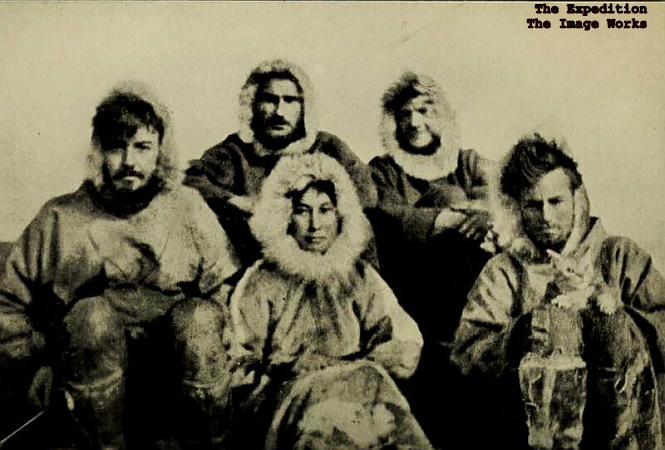

Alaska Nellie took everything by storm. Born Nellie Trosper, she learned to take the woods that way on a farm near St. Joseph Missouri. She trapped and, a terrific shot, she hunted. In her spare time she helped her parents raise 11 younger siblings.

As soon as her parents could spare her, though, Nellie headed west in search of new things to take by storm. Barely five feet tall with her shoes on, she worked her way west to Colorado then to California then, finally, to Seward Alaska in 1915.

Link to another story “Ada Blackjack—The Toughest Woman You’ve Never Heard About”

Alaska Nellie never looked back.

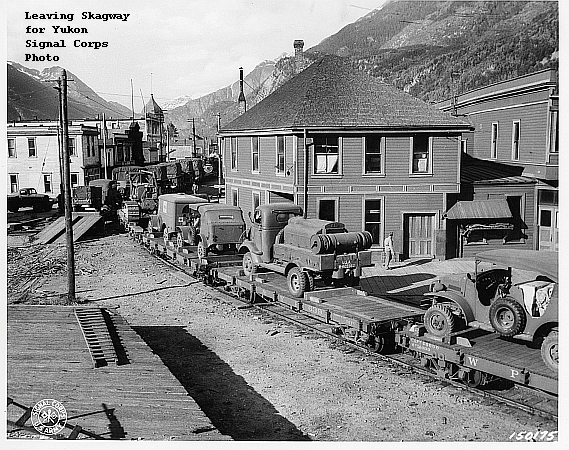

The Alaska Road Commission hired her to run a roadhouse to feed and house workers on the new Alaska Railroad. Nellie filled out the menu with her rifle in the woods. She got herself a dog team. She collected an amazing array of hunting trophies. And her legendary gift for story telling entertained her customers.

During a blizzard, when the local mail carrier failed to arrive at the station on time, with his sacks and pouches full of valuable mail, Nellie hitched up the dogs, backtracked to find him stuck and freezing to death. She took him back to the roadhouse to warm up and then delivered his mail to the waiting train. That exploit earned Alaska Nellie a medal from the town of Seward.

Nellie found her final home in a roadhouse where the railroad ran next to the blue-green water of Kenai Lake. When She married Bill Lawing, the railroad named its stop there “Lawing”.

Tourists stopped in Lawing to laugh at Nellie’s hilarious stories and eat delicious food from the surrounding woods and the roadhouse garden. Celebrities came to Lawing to experience the place. According to Patricia A. Heim, in her book, Alaska Nellie, “Her guest register of over 15,000 read like the Who’s Who of the early twentieth century: two U.S. Presidents, the Prince of Bulgaria, Will Rogers, authors, generals and many silent-screen movie stars.”

In 1956 Alaska designated an “Alaska Nellie Day”.

But when her spectacular life finally ended, they laid her to rest under a tombstone that read simply “Lawing”.

Writer Helen Hegener who penned an article for the Anchorage Daily News in 2014 that provided much of the information in this post, wrote the article to publicize a fund-raising project to provide Alaska Nellie with a suitable tombstone.