Racism complicated the management of the Epic Alaska Highway Project. Skin color repeatedly trumped every other consideration.

In June 1942 thousands of United States Army soldiers and thousands of civilian contractors from the United States and Canada sprawled across Northern Canada and Alaska; struggled to get organized and make progress on the desperately needed land route to Alaska. Japanese assaults in the Aleutians—at Dutch Harbor and Kiska and Attu—lifted the pressure on their commanders to a whole new level. More on the Japanese Assault

In the Southern Sector the 35th Engineers had come first to the project in March. In June they struggled through endless rain and mud north from Fort Nelson around and over Steamboat mountain More on Steamboat Mountain. The 341st Engineers had followed them through Dawson Creek and north to Ft St John, desperate to upgrade the winter-only trail north to Fort Nelson before the men of the 35th starved. The inexperienced soldiers of the 341st had endured a disastrous May, climaxing with hideous tragedy at Charlie Lake. More on Charlie Lake

In June Colonel “Patsy” O’Conner, Southern Sector commander, struggled to reorganize and recover. And the Corps sent him a tremendous asset—the 95th Engineering Regiment.

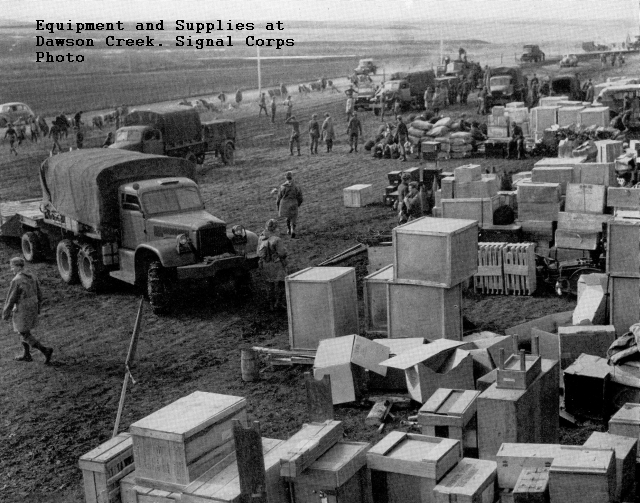

The soldiers of the 95th came to Dawson Creek with significant training and experience under their belts. Unlike so many of the regiments on the project, the 95th had jelled into a working team. They knew their job and how to do it. Moreover, their equipment followed close behind them—including heavy equipment.

But the soldiers of the 95th were black, and O’Conner couldn’t get by their color…

When the long string of flatcars bearing the 95th’s heavy equipment rolled into Dawson Creek, O’Conner had it unloaded and delivered directly to the white soldiers of the 341st.

The soldiers of the 95th came to the highway with two bulldozers, one grader, a carryall, less than twenty small dump trucks—and hand tools. O’Conner ordered them to fall in behind the 341st to clean up the roadway. The soldiers of the 95th swung picks and wielded shovels, hauled dirt with wheelbarrows and felled trees with axes and saws. And work for the 95th eventually ran out.

With little to do they found themselves occasionally serving as stevedores for the white rookies of the 341st. More often they simply remained in camp, surrounded by mud, huddled under rain-soaked canvas.

Froelich Rainey, visiting the highway in 1942 to report for National Geographic, hitched a ride out of Charlie Lake in a convoy of supply trucks piloted by members of the 95th. His young black driver wanted desperately to be home in Virginia in the “bright hot days of his homeland. This awful country, nothing but cold rain, mud and trees.” It took them six hours to travel 15 miles.

This history of rampant racism during the difficult and necessary job of building a road to Alaska should open everyone’s eyes. There isn’t one mention of this time at the Museum of African American History in Washington DC. If you go there please mention this to the museum director. Our young students deserve to know the whole truth when they learn about the sacrifices of our black citizens who built this important road.

Diana, you are dead on. I hope people follow your suggestion.

As a 17-year Alaskan I’ve driven and flown over the Alaska Highway a number of times. I can’t get enough of these great stories!

I can’t begin to tell you how much that means to me. We discovered Alaska and Northern Canada several years ago and we have been obsessed with it—two books, this blog, our research site. Thank you again for an enormous morale boost.

And I don’t mean to Be anonymous. I just forgot to typed that I’m Dennis.