How do you lose the remains of an honorably buried soldier? It’s not easy.

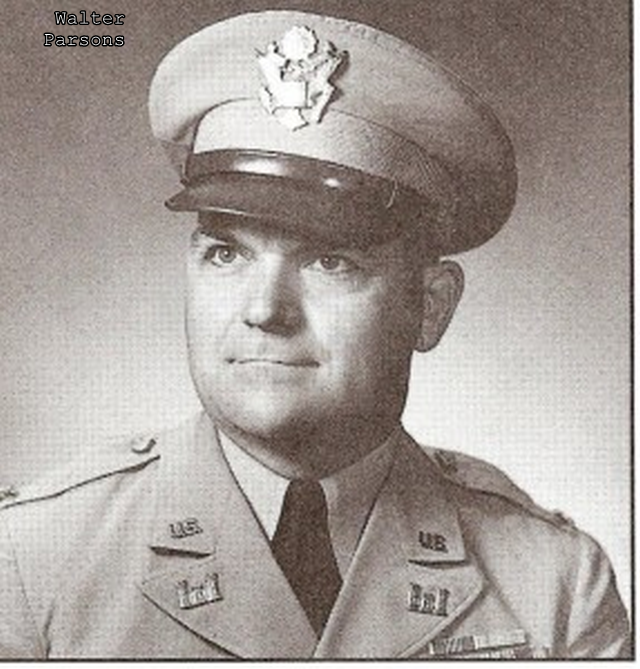

Last night I posted about Private Major Banks who, along with thousands of other soldiers, received a contaminated yellow fever vaccine in March 1942. In June Private Banks contracted serum hepatitis and at the end of June he passed away in the Valdez Hospital. To get the town to allow him to bury the soldier, Captain Parsons of the regiment convinced them to create a ‘negro’ section in their cemetery. Parsons laid the young soldier to rest with full military honors.

The fate of Private Major Banks.

A few days later, Parsons moved inland to take command of Company F and, with the rest of the regiment, worked far away from Valdez. In 1945, troubled by having a soldier’s remains in the civilian cemetery, an army official had him dug up and reburied in the post cemetery at Fort Richardson.

Private Banks’ mother got in touch and asked that her sons remains be shipped to her in Virginia so she could bury him near home. And in 1948 the Army honored her wish. Finally, truly “laid to rest”, Private Banks remains, as far as we know, have been undisturbed.

Fast forward to the 1990’s. Captain Parsons who finished the Highway Project with the 97th then moved on to the Canol Pipeline project and then moved on to other postings and duties had settled as Colonel Parsons, the ROTC Tactical Officer at his alma mater, Texas A&M. From that job he had retired.

An honorable man to his very core, Parsons remembers that young black man back in 1942. Did his grave ever get an appropriate marker? As far as he knows the remains remain where he left them. He pens a letter to the town council of Valdez to inquire and to offer to arrange for a headstone from the VA if necessary.

Parsons not only didn’t know the Army had moved the private twice, but also he didn’t know that a monumental tidal wave had literally wiped the town of Valdez from the face of the planet in 1964. The citizens had left the ruins behind and rebuilt their town on more stable ground a few miles away.

If Valdezians in the early 1940’s had to create a special ‘negro’ section on a bit of ground across a creek from the main cemetery to bury a black man, attitudes had changed a lot by the 1990’s. The Valdezians who received Parsons’ letter had no idea the cemetery at the old town site even had a ‘negro’ section. The letter set in motion years of fruitless attempts to identify the section and to locate the remains so they could properly memorialize the deceased soldier.

In 2017 Christine and I visited Valdez. Our book, We Fought the Road, had been released early in Canada and Alaska and through the summer we travelled through the north country on a publicity tour. Folks attending our appearance at the Valdez museum told us about the tidal wave and one gentleman offered to show us how to find the old Valdez the next morning.

We walked through the cemetery and he told us the story of the letter and the soldier and the town’s attempts to find the grave. He took us across the little creek to where they thought the ‘negro’ section might have been.

He knew nothing of the story, of course, except what they had read in Parsons’ letter—knew nothing of contaminated vaccine or serum hepatitis. Christine, the intrepid researcher on our writing team, promised to dig into the archives and find out what she could. Back in the lower 48 that fall, she did so and her research yielded the rest of the story.

Private Banks rests in peace. Honorable man, Walter Parsons, does the same. And Valdez is off the hook.